How in the name of science Haydn’s head was stolen from his grave

One of the customs that makes humans special in animal kingdom is the custom of burial or ceremony to say goodbye to the deceased. In fact, burial ceremonies and the traditions of afterlife are very much telling about the age, religion and social structure of a certain period and region. Throughout history, from ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, Persia or Greece one finds very interesting traditions related to burial, death and afterlife.

I myself always thought that regardless the ceremony or method of funeral (either burial or cremation most of the time), a human being who left the world of the living deserves rest in peace. I never approved of the excavation of graves. Certainly, to rob a tomb is evil, but even for the sake of history or science, for me it is beyond acceptable. The remains as skeletons or mummified bodies ending up in prestigious museums were human beings and just because they had died long time ago it does not mean we are free to expose and move them.

The case of poor old Joseph Haydn’s skull contains all these awful elements: human stupidity, justification with science and using earthly remains as home decoration.

The stealing of Haydn’s head

After a long period of illness Joseph Haydn died in 1809, at the age of 77. As Austria was in war with Napoleon and Vienna itself was occupied, not much attention was paid to the event and the funeral was modest.

|Related: more articles on Haydn

Two conspirators, Joseph Carl Rosenbaum (employee of Nikolaus II, Prince Esterházy) and Johann Nepomuk Peter (a prison director), bribed the grave digger Jakob Demuth to steal the head from the grave. The crime was done on June 4.

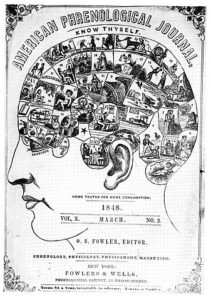

The two men were firm believers of a contemporary scientific movement called Phrenology. This, today discredited, movement expected that certain areas of the brain are responsible for certain cognitive functions and individuals using some areas more than others, will result in bigger muscle bumps on their skull in certain areas showing the extra activity. They believed the careful examination of a skull will tell personality traits. Although the idea certainly has seeds of truth in it, but the theory in its complete form, this kind of generalization was later proved baseless and a theory departed from science.

The head, due to the time passed since the death and the hot summer weather, was in miserable conditions. Reportedly, Rosenbaum got sick from the smell and sight as he was delivering the head to the hospital for the examination. This dark act justified in the name of science resulted only a one-hour long ‘study’ of the skull, then it was macerated and bleached. The whole evil enterprise was concluded in this finding: the bump of music on Haydn’s head was indeed fully developed.

The skull was placed in a custom-made black wooden box, with cushion and a little window. First, it was in the possession of Peter (who had a collection of skulls), later was given to Rosenbaum. The theft was more or less a secret of a chosen few, until in 1820 Haydn’s old patron Prince Nikolaus Esterházy II decided to bring the earthly remains of Haydn to his estate at Eisenstadt. During the exhumation just a body and a wig was found…

After a short investigation Rosenbaum and Peter were named as responsible. Through a series of lies and deceit they kept the original skull and gave the Prince a false one. Haydn was buried again, but with a foreign skull.

When the two criminals had passed the original skull was given from hand to hand. It took a hundred years to finally stop this madness. In 1932, Prince Paul Esterházy built a marble tomb for Haydn at the church of Eisenstadt (Bergkirche) and expressed his wish to unify the body. The last ‘owner’ of the skull, the Society of the Friends of Music in Vienna, agreed but for all kinds of delays the skull only returned to the body in 1954. Strangely, the substitute skull was not removed at the unification and Haydn’s tomb now contains two skulls.

Another master of music suffered similar fate, Mozart. His grave was unmarked for a long time (more than 50 years) and according to the myth only the grave digger knew the exact spot. His skull was stolen and only after a century it ended up in the Mozarteum in Salzburg. The DNA test carried out on the skull in 2004 (which is missing its lower jaw) was inconclusive.

Despite the publicity of both cases it seems followers of Phrenology and other tomb raiders were still active at the time of Beethoven’s death. After his burial the grave digger from Wahring cemetery reported to Schindler (Beethoven’s self-appointed secretary) that he was approached and offered 1 000 florins for the composer’s head. They had notified the police and according to our best knowledge his body remained intact in his grave to this day (apart from the damage caused by autopsy).