In part 2 of this three-part interview, Jonathan shares with us his story of how he became the editor of the Bärenreiter urtext editions of Beethoven’s nine symphonies.

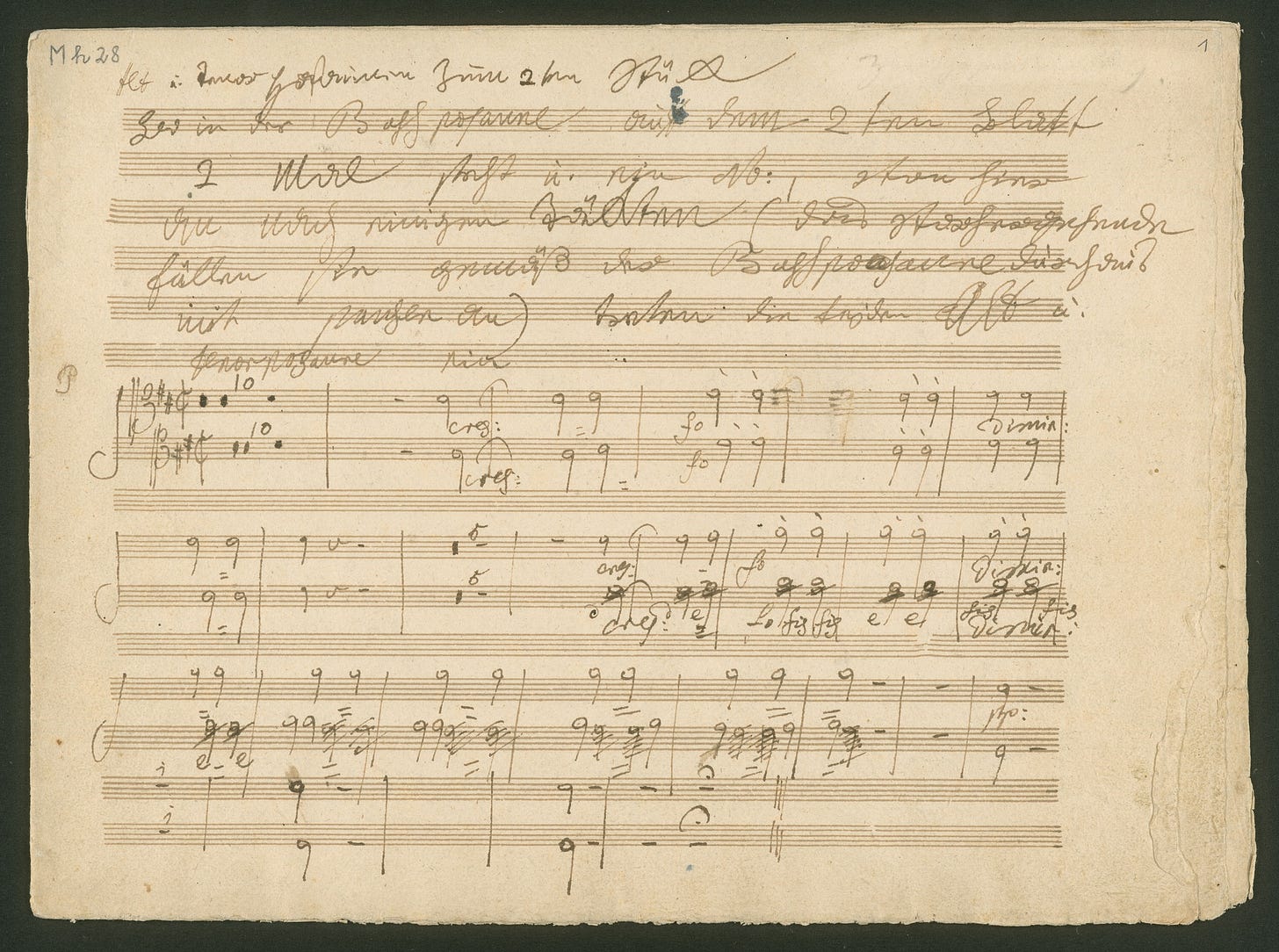

In our previous article, Deciphering Beethoven, we learnt from Beethoven scholar, Jonathan Del Mar, just how meticulous Beethoven’s notations were, despite the rather widespread criticism the composer has received for his untidy handwriting.

Jonathan Del Mar’s journey as an editor began in his father’s company, studying Beethoven’s scores together in their drawing room, fascinated by the differences between editions, trying to decipher what the composer’s final intentions were.

Jonathan, it is a joy to gain such detailed insight into Beethoven’s autographs, and interesting to learn how much variation exists between different publications. Will you share with our readership what this work involved, and what discoveries you made along the way, with respect to Beethoven’s scores?

I first really studied a Beethoven autograph seriously in 1984, when my good friend Caroline Brown (we were in the Hertfordshire Youth Orchestra together, both cellists, we even shared a desk for a time) brought out a record (LP, of course) of the Fifth, proudly labelled “authentic – first recording ever on original instruments!” with her own orchestra, the orchestra she created, the Hanover Band. Well I reckoned I knew a few textual problems in that piece, and she says “authentic” – let’s see! So I went to the British Library and requested to see the facsimile of Beethoven’s autograph. And although I did already know that you have to be careful, “the autograph is not always the last word!”, there were clearly a few hundred cans of worms which this new “authentic recording” had not even looked at, they just played the text in any old modern edition. So I confronted Caroline with my (albeit rather embryonic) findings, and bless her, what did she say but “We’re doing the Fourth next; would you like to go to Berlin at our expense and look at Beethoven’s autograph for us?” Wow. So that was the first time – 1985 – that I actually had a real live Beethoven autograph in my hands. It does give you a bit of a wobbly feeling.

But still, I knew nothing of the necessity of examining the full network of sources. I found a copy of the first edition score (published as late as 1823, so hardly authentic), compared it with both the autograph and the modern editions, and came away with a whole load of problems, some of which I could solve, others only guess at. But it was a beginning. Next she sent me to the Beethoven-Haus in Bonn to look at the Pastoral, and that was very exciting because there was one more source to look at: the copyist’s manuscript used as Stichvorlage (printer’s model) for the first edition. Two things about that: firstly it was a new discovery; this was now 1986, and just two years earlier it had been found totally by chance in a private collection in Bavaria. It had been in the big floods of 1953 in Holland and was water-damaged, but only seriously (so that notes are illegible) in the last few pages of the finale. No one had really studied it in detail before.

Second: the first edition, I now discovered, was not an 1820s score at all – that is of no consequence; it was a set of parts published in 1809. So I now had quite a network of sources to compare, and it was exciting to discover that the violins are muted (con sordini) throughout the slow movement; the first copyist remembered to add it in two other manuscripts he copied at the same time, but in that vital Stichvorlage manuscript he just forgot, with the result that it had been missing ever since.

And then we did the Eroica together, and then the Violin Concerto; and each time I found out about more of the ‘missing links’ between autograph and first edition, all the different manuscripts you have to look at in order to reconstruct – to go back to those sessions with my father all those years ago – what went wrong, where, and why. Who misread what – or whether Beethoven changed his mind. The astonishing thing, after so many years, is just how much survives – how often, if you call up the right manuscript and study it carefully, you can still see Beethoven revising a note or a passage from this to that. In the Violin Concerto this is of the greatest importance; the autograph only shows embryonic versions of the articulation, and it may be tempting to just say “this obviously doesn’t work – clearly Beethoven didn’t really make a final decision – that means we can do anything we like!”, and invent slur-patterns which Beethoven would have hated. If we just look at the Stichvorlage manuscript – copied by that same copyist we met in the Pastoral – we can see Beethoven’s meticulous corrections wherever something was not absolutely precisely right, and in that manuscript the slurs are both completely different from what was in the autograph, and totally organised. We know Beethoven revised all the articulation, and what is in the copyist’s manuscript is what he wanted. But there was something else there, too! In bar 463 of the first movement, in the middle of a continuous run of 16ths, the copyist (he was a very good copyist, but no one is infallible) had suddenly written a quaver (8th) G at the beginning of the bar. Beethoven added the missing B before it (to complete the run), and made one of his characteristic correction marks “+ h” in the margin, but alas! – the copyist misunderstood the correction, and changed the quaver to B instead of adding the B to make two 16ths. So ever since, we have heard a sudden plonk – stop – in the middle of this otherwise fluent run, and on a totally illogical B!

And then, Caroline summoned me and took a deep breath – this was the big one – in April 1988 they were going to record the Ninth. Golly. For this crowning masterpiece I decided that nothing less than the ultimate job of work would do: I had to ferret out every source I could, check every note, dot and slur, and do an absolutely complete job of work as far as I was conceivably able. We only had six months in which to do it; but by doing nothing else at all I just about managed it, together with trips to Berlin, Mainz, Aachen and Vienna to see all the secondary sources, all of which contain essential pieces of this extremely complex puzzle. I started by checking every detail of the autograph, which it seems no one had ever done before – extraordinary, that, when you consider (a) how supremely important this piece is; (b) that the facsimile had been available these sixty years; (c) that there were no end of known textual problems which conductors all over the globe were wanting answers for; and (d) that Urtext Editions had already been done for virtually the complete works of Bach, Handel, Haydn, Mozart and Schubert. Why hadn’t anyone looked at this stuff? The answer lies partly in politics.

Many Beethoven manuscripts, including the Ninth but also the Seventh and many other works, had gone missing since the war; they had been spirited out of Berlin by the Nazis – one of the few good things they did! – in order to save them from the bombs. And indeed, only a few weeks later the Berlin library that had housed them, the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, was reduced to rubble. So where were they? The whole story is told in riveting style – this is such a good read! – by Nigel Lewis in his 1981 book Paperchase. Briefly, they were in a part of the former Grossdeutsches Reich that lay so far east that it was yes, safe from the bombs, but what the Nazis couldn’t have guessed is that unfortunately after the war it would no longer be Germany! So they were rescued from a monastery crypt by the locals in about 1970, taken to the Jagiellonian Library in Krakow, and there (this was of course the Cold War) left to sit around. But gradually word seeped out, and by about 1975 it became known among exalted circles in the West (the British Council, for example) that there was something very exciting lurking but which the Poles were guarding with their very lives. In 1977 the German government did a deal with them; they gave them three million marks in exchange for some of the manuscripts that were deemed absolutely central to German culture, including the Ninth Symphony, and that is how the Ninth, at least, now resides in Berlin. But many remain in Krakow, and some printed editions that were in the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin even ended up in Russia and to this day we don’t know exactly where they are. So, I suppose it would have been impossible to do an Urtext Edition of the Ninth much earlier than when I came on to the scene; I was just incredibly lucky to be there at the right time.

‘I was terrified; who am I to be making such far-reaching changes to this iconic work, already cherished and sanctified by millions across centuries?’

To return to the story of the Ninth! Checking every detail of the Ninth brought me out in a cold sweat; there was just so much that had evidently been simply misread ever since. These were not Beethoven revising the text later. From little things like bars 16, 18 and 52 where the second flute notes were in the wrong octave, bar 51 2nd Horn wrong octave, to more important things like the 3rd and 4th horn entry missing entirely in bar 29, and the flute and oboe note in the main second-subject tune in bar 81 was wrong – just the first hundred bars had so many world-shattering corrections that either I was a monkey and had no idea what I was doing, or this piece had been significantly misrepresented all these years. So I ploughed through, emerging with hundreds of pages of foolscap covered with presumed corrections, and set off to study all the copyist’s scores in various cities around Europe (just one, in the British Library, was only a bike ride away). And in Mainz I struck gold: here at last was the Stichvorlage copyist’s score absolutely seething with Beethoven’s revisions and corrections; here was the authentication of all those myriad important differences (such as that long D in the Trio) between the autograph text and that in modern editions. Or most of them! Annoyingly, frustratingly and mystifyingly, that long D was not replaced by anything in Beethoven’s handwriting, but instead just that page was written by a different copyist, very neatly but suddenly with no corrections by Beethoven, and moreover a text that could not possibly be correct because it was totally inconsistent and illogical.

So what do we do now? There was just one more port of call, which I had previously ignored, partly because it was in Berlin where I had been so busy with the autograph that a few odd pages of copyist’s score (that’s all it was) could hardly compete in importance. But now that I looked at them, with the knowledge of what was in Mainz, the fog all cleared, here was the solution staring me in the face, and it survived all these years!! Here was Beethoven revising the long D to pairs of tied notes, everything was crystal clear – but it was a bit of mess, and the poor publishers, in their wisdom, decided the page had to be recopied so that it was clearer for the printer. And unfortunately the copyist they contracted to do the work was one who was an ass (literally – that is what Beethoven called him, Esel). And he made mistakes in nearly every bar. And that is why these bars in the violins (that’s 503-6, 515-22) have been played totally wrong ever since – due to the idiocy of that one bad copyist.

And then there was the absolute most world-shattering revelation of all, one that had Simon Rattle on the phone to me as soon as he received the correction list: the added ties in the Horns in bars 532-40 of the Finale. These are at once so fascinating yet so bizarre, so disturbing yet so conclusive, that they literally change our understanding of this section of the movement. I was terrified; who am I to be making such far-reaching changes to this iconic work, already cherished and sanctified by millions across centuries? But the evidence was there in black and white, and it seemed I had no alternative but to print and let damnation come if it will.

And so the Hanover Band put out its recording, and musicians started to get interested – it was a big moment in 1991 when the phone call came from John Eliot Gardiner. Then Sir Charles Mackerras declared his interest; and then, finally, in 1994 Roy Goodman (of the Hanover Band) was talking to Patrick Abrams of Bärenreiter – Patrick does sterling work, talking to conductors all over the globe gaining insights into their concerns and requirements – and it all went from there. It has to be said that I was not the only one who was terrified whether I would be exposed as a know-nothing charlatan – Bärenreiter were also dead scared – but thankfully the reception was unanimous and we went on to cover most of the remainder of Beethoven’s most important works. Except Fidelio – that piece is a textual nightmare and I have always said it would require another whole lifetime in order to do justice to that minefield.

Look out for part 3 of this interview, titled: A life immersed in music!