At the time of Beethoven Vienna was full of talented musicians. Some of them extraordinary, but very few were favorably compared to him – especially with the piano. There was one exception…

Who was Joseph Woelfl?

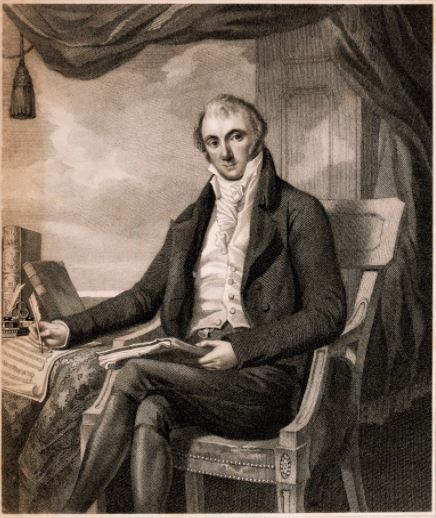

Joseph Johann Baptist Woelfl (surname sometimes written as Wölfl or Wölffl) was a pianist and composer from Austria (24 December 1773 – 21 May 1812). He was born in Salzburg (hometown of Mozart), where he was the pupil of Mozart’s father Leopold Mozart and Michael Haydn, the younger brother of Joseph Haydn. His first public appearance was at the age of seven, and his instrument was a violin.

As a contemporary, just as Beethoven, he also gravitated towards Vienna, the musical capital of the world at that period. He moved to Vienna in 1790, where his first opera (Der Höllenberg) was staged in 1795. Here, with the recommendation of Mozart, he was introduced to the Polish count Oginsky. This count took him to Warsaw, where as a piano virtuoso and composer, he enjoyed unprecedented success.

Nature was generous with Woelfl! He was a tall man, but most importantly had large hands with long fingers (according to Václav Tomášek his fingers were monstrously long). Combine it with exceptional musical talent and you get a perfect piano virtuoso!

He later moved to Paris and stayed there between 1801 and 1805. Next year he moved to London, where he lived until his death in 1812.

His compositions were somewhat forgotten until the new millennia, when his piano sonatas and concertos were recorded and published again.

Beethoven vs. Woelfl

Most accounts on Beethoven’s piano performance emphasize his unique talent and the extraordinary emotional impact he had on his audience. The usual argument is that at his zenith there was no one even comparable to him. Maybe, there was one exception…

Woelfl and Beethoven had good relationship. They both arrived to Vienna about the same time and both enjoyed the attention of the same music aficionados. It was only natural that audience soon began to divide and fan clubs gathered around each musician. The question was: who is better, Beethoven or Woelfl?

In an article in the Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung (April, 1799) a writer describes the differences as the following:

“Opinion is divided here touching the merits of the two; yet it would seem as if the majority were on the side of the latter (Wölffl). I shall try to set forth the peculiarities of each without taking part in the controversy.

Beethoven’s playing is extremely brilliant but has less delicacy and occasionally he is guilty of indistinctness. He shows himself to the greatest advantage in improvisation, and here, indeed, it is most extraordinary with what lightness and yet firmness in the succession of ideas Beethoven not only varies a theme given him on the spur of the moment by figuration (with which many a virtuoso makes his fortune and—wind) but really develops it. Since the death of Mozart, who in this respect is for me still the non plus ultra, I have never enjoyed this kind of pleasure in the degree in which it is provided by Beethoven.

In this Wölffl fails to reach him. But W. has advantages in this that, sound in musical learning and dignified in his compositions, he plays passages which seem impossible with an ease, precision and clearness which cause amazement (of course he is helped here by the large structure of his hands) and that his interpretation is always, especially in Adagios, so pleasing and insinuating that one can not only admire it but also enjoy…. That Wölffl likewise enjoys an advantage because of his amiable bearing, contrasted with the somewhat haughty pose of Beethoven, is very natural.”

Another detailed report on this special rivalry and these two extraordinary pianists comes from Ignaz von Seyfried. Seyfried was a famous conductor in Vienna, regular guest at Viennese musical events. He reaches a very similar conclusion in his recollection decades later, saying

“Beethoven had already attracted attention to himself by several compositions and was rated a first-class pianist in Vienna when he was confronted by a rival in the closing years of the last century. Thereupon there was, in a way, a revival of the old Parisian feud of the Gluckists and Piccinists, and the many friends of art in the Imperial City arrayed themselves in two parties. At the head of Beethoven’s admirers stood the amiable Prince Lichnowsky; among the most zealous patrons of Wölffl was the broadly cultured Baron Raymond von Wetzlar, whose delightful villa (on the Grünberg near the Emperor’s recreation-castle) offered to all artists, native and foreign, an asylum in the summer months, as pleasing as it was desirable, with true British loyalty.

There the interesting combats of the two athletes not infrequently offered an indescribable artistic treat to the numerous and thoroughly select gathering. Each brought forward the latest product of his mind. Now one and anon the other gave free rein to his glowing fancy; sometimes they would seat themselves at two pianofortes and improvise alternately on themes which they gave each other, and thus created many a four-hand Capriccio which if it could have been put upon paper at the moment would surely have bidden defiance to time. It would have been difficult, perhaps impossible, to award the palm of victory to either one of the gladiators in respect of technical skill.

Nature had been a particularly kind mother to Wölffl in bestowing upon him a gigantic hand which could span a tenth as easily as other hands compass an octave, and permitted him to play passages of double notes in these intervals with the rapidity of lightning. In his improvisations even then Beethoven did not deny his tendency toward the mysterious and gloomy. When once he began to revel in the infinite world of tones, he was transported also above all earthly things;—his spirit had burst all restricting bonds, shaken off the yoke of servitude, and soared triumphantly and jubilantly into the luminous spaces of the higher æther. Now his playing tore along like a wildly foaming cataract, and the conjurer constrained his instrument to an utterance so forceful that the stoutest structure was scarcely able to withstand it; and anon he sank down, exhausted, exhaling gentle plaints, dissolving in melancholy. Again the spirit would soar aloft, triumphing over transitory terrestrial sufferings, turn its glance upward in reverent sounds and find rest and comfort on the innocent bosom of holy nature. But who shall sound the depths of the sea? It was the mystical Sanscrit language whose hieroglyphs can be read only by the initiated.

Wölffl, on the contrary, trained in the school of Mozart, was always equable; never superficial but always clear and thus more accessible to the multitude. He used art only as a means to an end, never to exhibit his acquirements. He always enlisted the interest of his hearers and inevitably compelled them to follow the progression of his well-ordered ideas.”

Unlike the case of the duel with Stiebel, this relationship remained friendly. Both respected the other. Seyfried describes the mindset of the two and writes

“They respected each other because they knew best how to appreciate each other, and as straightforward honest Germans followed the principle that the roadway of art is broad enough for many, and that it is not necessary to lose one’s self in envy in pushing forward for the goal of fame!”

As a sign of true respect Woelfl dedicated his Piano Sonata in A minor, Op.6 (1799) to Beethoven.