Beethoven was blessed to have many excellent teachers and mentors, but nobody was so influential in his life than Christian Neefe.

Who was Christian Gottlob Neefe?

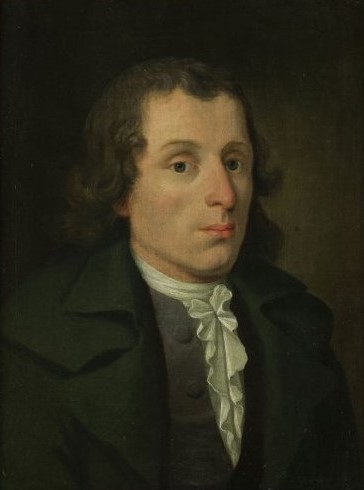

Christian Gottlob Neefe (5 February 1748 – 28 January 1798) was a German musician and composer, who also was a writer.

Neefe was born in Chemnitz, Saxony, into a poor family. His musical talent and passion was evident from early childhood, he started composing from the age of 12. At first, he tried his luck with law as a profession, mainly to satisfy his parents. He studied at the university of Leipzig for seven years, graduated successfully, but eventually he returned to music and became the pupil of Johann Adam Hiller (composer, conductor and father of early German opera). His first works were comic operas, but during his career he composed concertos, sonatas, and even translated librettos. He inherited Hiller’s musical director position in Abel Seyler’s theater in Dresden.

Later, he moved to Bonn to become the music director of G. F. W. Grossmann’s theater, that was practically the court’s official theater at the time. In Bonn, he met and mentored young Ludwig van Beethoven.

Neefe was enthusiastic about the Enlightenment, he was a Freemason and member of the Illuminati. As a religion, in his adulthood he became a Calvinist, however in Bonn he baptized his children as Catholic. Apart from music he was a writer (mainly a poet, enthusiast for German folk poetry) and a biographer. He was married, his wife was a singer from Leipzig. Neefe died impoverished in Dessau, in 1798.

His legacy in Germany was significant, both in music and in literature.

Neefe, Beethoven’s most important teacher

It was young Beethoven’s father who first met and introduced Neefe to his son. He heard about this newly arrived court theater director from Grossmann. The human connection was evident from the start and Beethoven became the pupil of Neefe from 1781 (age 10).

Neefe’s musical orientation and taste was rooted in Leipzig and in the two towering figures of this town, J. S. Bach and his son C. P. E. Bach. When Neefe was a student in the city, some of the pupils of the elder Bach were still active. (Similar to Brahms, when he arrived to Vienna and encountered with musicians who eye – or ear – witnessed Beethoven). Developing Classicism and early Romanticism, the emphasis on the emotional element of music, was paramount in their work. Through Neefe these ideas reached and formed Beethoven in a significant way. Not only musical ideas that Neefe introduced to his young student. Literature too, especially of Goethe and works from Schiller.

It was Neefe himself, who in 1783 published an article in Cramer’s Magazin der Musik about young Beethoven’s very first published work. The article is in third person and says,

“Louis van Betthoven, son of the tenor singer mentioned, a boy of eleven years and of most promising talent. He plays the clavier very skillfully and with power, reads at sight very well, and … plays chiefly The Well-Tempered Clavier of Sebastian Bach, which Herr Neefe put into his hands. Whoever knows this collection of preludes and fugues in all the keys – which might almost be called the non plus ultra of our art – will know what this means. … He <Neefe> is now training him in composition and for his encouragement has had nine variations for the pianoforte … engraved in Mannheim. This youthful genius … would surely become a second Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart were he to continue as he has begun.”

Many consider the fact mentioned in the article, that he made Beethoven study and play the Well-Tempered Clavier, was the most important act Neefe ever did for his young protégé. He also introduced the boy to the rich German music literature, not evidently available in courts favoring Italian music.

Parallel to practicing the clavichord, later the piano, Neefe also helped the young man in compositions. On the playing part Beethoven was impressive from the start. At the age of eleven, Neefe was so confident of the boy, that when he left the town on official duties, he entrusted his organist position to Beethoven. The jump-in turned out to be so successful, that soon he was a regular substitution, later official assistant, not only at the chapel organ, but also in the theater and in the court orchestra.

This flourishing life came to an end when Elector Maximilian Friedrich died in 1784. Grossmann and his theater left Bonn, and the court musicians, as it was customary at an elector’s death, were let go. The new regime rehired the ones they liked, both Neefe and Beethoven were among them. Despite this, Neefe was actively looking for new opportunities, somewhere else.

When Beethoven left Bonn for Vienna, Neefe again published an article, this time in the Berliner Musik-Zeitung:

“Ludwig van Beethoven, assistant court organist and now unquestionably one of the foremost pianoforte players, went to Vienna at the expense of our Elector to Haydn in order to perfect himself under his direction more fully in the art of composition.”

Probably, one can never fully grasp the influence of a good mentor and teacher, the imprint we carry all our life. Beethoven knew he had one and in a letter he wrote Neefe, “I thank you for your counsel very often given me in the course of my progress in my divine art. If I ever become a great man, yours will be some of the credit.”