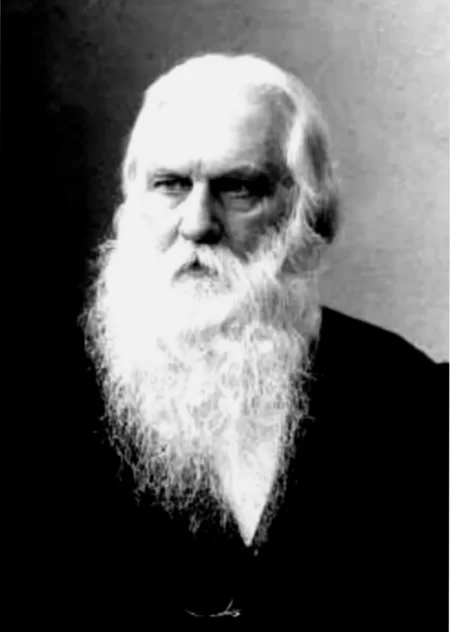

Alexander Wheelock Thayer (1817-1897) was an American writer and journalist who travelled to Europe to conduct extensive research on Beethoven’s life, with the intension of writing the first scholarly biography of the great composer. His work became the basis for modern research on Beethoven.

Thayer was born in South Natick, Massachusetts. He attended Harvard college, and it was whilst he was working in the Harvard library that he became interested in Beethoven and began his research into the composer. He noticed a number of inconsistencies in Anton Schindler’s biography, and this prompted him to pursue the truth. The other extant biographical text at the time had been written by Franz Wegeler and Ferdinand Ries. It was published in 1838, and is considered highly reliable. It is a joint reminiscence, a collection of many anecdotes and copies of correspondence.

Thayer was a musical individual. He had tried his hand at composing, although he didn’t play an instrument, and had written many articles on music-related subjects.

In 1849, Thayer travelled to Europe and began his reasearch into the real Beethoven, learning German simmultaneously. His journalism, writing articles for the Boston Courier on European life and later, his position as US Consul in Triest between 1862-1882, enabled him to undertake this momentous task.

The biography: Life of Beethoven

The first edition of his biography was published in German, and was made up of three volumes. It was important to Thayer to publish the text in Beethoven’s own language too, in German. These covered Beethoven’s life up until 1816. After his death, his biography was completed by two of his German colleagues, both musicologists: Hermann Deiters (who was also responsible for the German translation) and Hugo Riemann, who completed the volumes after Deiter’s death. Riemann produced volumes 4 and 5, staying true to Thayer’s notes, which detailed Beethoven’s life between 1817 and his death a decade later.

‘I fight for no theories, and cherish no prejudices; my sole point of view is the truth…’ – Thayer

Thayer set the standard for modern biographical writing in terms of both accuracy and analysis.

Two further trips to Europe

Thayer spent two and a half years in Europe whilst researching Beethoven’s biography, up until his money ran out. He returned to America and worked for the New York Tribune until 1854, when he journeyed to Europe again to continue his research. A couple of years later he was back in America again, where his employer took an interest in his work and secured funding for his final journey to Europe to resume his important and admirable work.

Who did Thayer interview?

Life of Beethoven is an invaluable biography, as Thayer used primary sources for his work, interviewing people who had known the composer first hand. These people included Anton Schindler, his secretary; composer and friend to Beethoven Anselm Hüttenbrenner, who was at the composer’s deathbed; pianist and educator Cipriani Potter and Caroline van Beethoven, widow of Beethoven’s Nephew Karl. Thayer also looked through newspapers, obtained court records and analyzed conversation books that Beethoven had used to communicate with when his hearing deteriorated. He collected information that could be further analysed by scholars, which may otherwise have been lost forever.

The first English edition

In 1921, the first English publication of Life of Beethoven was produced, by Thayer’s American editor Henry E. Krehbiel.

Krehbiel writes in the introduction:

‘In it is told for the first time in the language of the great biographer the true story of the man Beethoven—his history stripped of the silly sentimental romance with which early writers and their later imitators and copyists invested it so thickly that the real humanity, the humanliness, of the composer has never been presented to the world. In this biography there appears the veritable Beethoven set down in his true environment of men and things—the man as he actually was…’

By the time the English edition was published, a great number of scholars had pursued research avenues opened up by Thayer and the resources he had unearthed, and these were added to the biography. Krehbiel writes:

‘His industry, zeal, keen power of analysis, candor and fairmindedness won the confidence and help of all with whom he came in contact except the literary charlatans whose romances he was bent on destroying in the interest of the verities of history.’

Poor health and migraines meant that Thayer wasn’t able to continue his work on Life of Beethoven with the same energy as in those first few decades; the tremendous effort that it took had in a sense resulted in a kind of saturation and Thayer occupied himself with other writing tasks alongside his work on the biography.

Some of these other texts include essays, children’s stories, and a book about the Exodus of the Isrealites from Egypt.

Thayer died in 1897, in Trieste. Some 60 years later a historian and an employee of the American consulate found Thayer’s forgotten grave. With the help of various Consuls, great care was taken to ensure the grave was restored and paid for into the future, honouring the man to whom we owe a debt of gratitude. Without Thayer’s tireless efforts, we would not know the veritable Beethoven!

A.K.