This magazine can not be complete without a comprehensive biography of Ludwig van Beethoven! Reading this biography is highly recommended as a start, but please visit our further articles as well! We keep publishing these regularly, with focus not only on his music, but on people, events and stories shaping him, revealing his character, beliefs and values!

Mozart’s spirit from Haydn’s hands

Music of the middle period – the World blown away

Birth, family

Ludwig van Beethoven – presumably – was born on 16 December 1770, in Bonn. What we know as a fact is the date of his baptism, which took place on the 17. at the Parish of St. Regius. Since in that era in Catholic Rhine country children were baptized on the next day following birth, this date is the best we can offer.

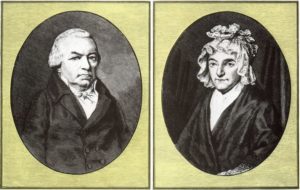

His mother was Maria Magdalena Keverich, daughter of a chef at the court of Trier. His father was Johann van Beethoven, son of Ludwig van Beethoven. Ludwig, the Elder, was originated from Mechelen (now Belgium) and was 21 when moved to Bonn, where he first had served as bass singer at the court of the Elector of Cologne, later raised to the rank of Kapellmeister (music director).

They say genes sometimes jump a generation, which is certainly true in the case of the Beethoven family. Grandfather was a talented and very well respected musician in Bonn. His son, Johann, however inherited little of the talents and all his life was a mediocre figure on the horizon of Bonn’s musical life. The famous grandson kept a portrait of his grandfather in his room all his life as a reminder of his musical roots and heritage.

Maria and Johann had seven children, sadly only three lived through infancy. Ludwig, the second, and two younger brothers, Kaspar Anton Karl and Nikolaus Johann.

The couple had a poor marriage, leaving Maria in the constant state of sadness and bitterness. Johann over the years became an alcoholic, an abusive father, a bad husband, overall a person without values. Experiencing all these Beethoven had grown to hate his father, which feeling accompanied him for the rest of his life.

More about Beethoven’s ancestry here!

Childhood

As a young boy, Ludwig had a difficult life. The Beethoven house was a sad place for both parents and children. His father Johann (a court singer at the time, mainly due to the family name) started the musical education of the boy. The teaching was rather a torture with rigid and brutal sessions. He had to stand on a footstool to reach the keyboard, his father standing next to him beating him for every mistake. Johann, coming home regularly late night, heavily drunk, usually woke Ludwig and made him practice. Such late night sessions were often kept by a certain Tobias Pfeiffer, a pianist and family friend, who reportedly suffered from insomnia. Beethoven, also learned to play the organ, violin and viola. Despite the stress and suffering during the classes, he showed extraordinary talent for music early on.

The boy often escaped the troubles at home and on such occasions he visited his friends at the von Breuning house, where the mother Helene took care of the youngster. It was she who first realized that Ludwig sometimes is having seizures, his attention wondering off even in the middle of a conversation. Upon returning the boy reported hearing music during such occasions.

As the grandfather’s financial heritage was running out, Johann started to promote Ludwig as a young prodigy, trying to emulate the – financial – successes of Leopold Mozart, father of Wolfgang. He even lied about the boy’s correct age, saying he was just six at his first public concert (March 26, 1778) – just as Mozart had been at his debut for Maria Theresia.

In school, as often the case with geniuses, he was having hard time to keep up with the class. Understanding and making multiplications or divisions was beyond his skill set, even as an adult. Facing realities and the above mentioned financial difficulties, he was withdrawn from school at the age of 10.

After school, Beethoven’s most important and most influential teacher in this period was Christian Gottlob Neefe. The man was the court’s organist, who taught him keyboard, composition and even helped him to get his first unpaid and later paid employment, as his assistant organist. Equally important, Neefe shared with him the ideas of the Enlightenment, the values of the French Revolution and the philosophies of the era’s modern thinkers. Beethoven not only enjoyed the discussions, but these became his most important values in his adult life. Neefe and many others around the teenager were freemasons and members of the Bonn lodge. Although he was familiar with the teachings, he never joined the order.

Beethoven’s first composition was the Nine Variations on a march (WoO 63). He was 11 years old at the time. It was published in 1782 (or latest early 1783) by Johann Michael Götz, in Mannheim.

End to a childhood

By this time a new Elector of Bonn was named, Maximillian Francis, who was the youngest son of Empress Maria Theresia. Just as his brother Joseph in Vienna, he made important changes and reforms in Bonn. Among these was the bigger attention and budget aimed at supporting arts. The new elector promptly realized the boy’s potential and backed his studies by sending him to learn in the capital of music, Vienna.

This first Vienna trip was a short one. It is not possible to know certainly, what happened during these few weeks, whom he met and if there were any lessons taken from Mozart. There is a myth without historical evidence that Beethoven in fact met Mozart, who upon hearing him play said “Keep your eyes on him; some day he will give the world something to talk about.” On the other side, Beethoven was not so impressed by the keyboard play of Mozart – which is just another legend without reliable background.

Beethoven, just as much as he hated his father, he loved his mother. As he learned she was ill, immediately returned to Bonn. She died of tuberculosis soon after, at age 40.

His father, never a strong character, sunk into an even deeper alcoholism, leaving young Beethoven in a position to take care of the family, especially the younger brothers. He stayed 5 years in Bonn and fulfilled his family duties in a very matured way.

During this period he earned the respect of the Court and became the most important asset in Bonn’s music repertoire. He spent more and more time at the Breuning house, escaping his father, where he taught the girls piano and he was introduced to German and classic literature. He also met influential supporters, among them most notably Count Ferdinand von Waldstein – a life long friend.

In 1789 he requested and was granted a legal order to receive half of his father’s salary paid directly to him, in order to be able to support the family. As his father was a disgrace not only to the Beethoven name, but to the whole Court of Bonn, the Elector was also willing to exile Johann to a village (we do not know with absolute certainty whether this exile has actually taken place or not). In one version of the story the father begged the son not to complete his humiliation and agreed to hand over the half salary himself. To this Ludwig agreed and his father kept his word. Johann van Beethoven died in 1792, causing great revenue fall in the liquor tax – as the Elector later joked about it cynically.

Mozart’s spirit from Haydn’s hands

In the coming two years (1790-1792) Beethoven composed his first bigger compositions. These were not published at the time and today music lovers can find them under WoO numbers (works without opus number). His first commissioned piece came in 1790, when Joseph II. died and he was – with the recommendation of Neefe – requested to score a cantata in the emperor’s memory. Soon the next sponsored music followed for the subsequent accession of the new emperor, Leopold II. These cantatas were numbered as WoO87 and WoO88, the Emperor Cantatas. Unfortunately, at the end they were not performed and were basically unknown to the public until the 1880s.

As Haydn was recently freed from the service of the Esterházys, he was longing to visit London and make himself a fame and some considerable amount of money. On his way to Britain he stopped at Bonn and the two men were introduced. Haydn stopped again at the return journey and during this second time arrangements were made by the Elector and Count Waldstein, to send Beethoven to Vienna once more in order to learn music from the old master. Papa Haydn, as he was called by his students, was known for having a gentle and gracious heart to everyone, especially talented young musicians, agreed to this scholarship. He had no idea what he was getting into…as later Beethoven turned out to be an inpatient and ungrateful student.

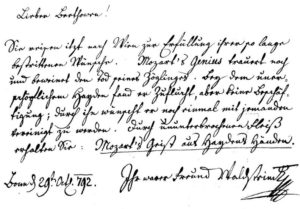

In 1792 the time had come to say goodby and start the next chapter in his life. Beethoven had many entries in his friendship book, but by far the most famous was written by Count Waldstein: “Dear Beethoven! You go to realise a long-desired wish: the genius of Mozart is still in mourning and weeps for the death of its disciple. (…) By incessant application, receive Mozart’s spirit from Haydn’s hands.”

Early years in Vienna

Before looking at his first years in Vienna, it is important to consider the background he is bringing with himself to the capital of the Empire. During the reign of Maximillian Francis, Bonn was transformed from a provincial town to a flourishing and cultured capital city. The city was under strong French revolutionary influence in every possible way, including music. Another strong music influence was the so called Mannheim School and their approach to orchestra and music in general. Both had determinative power on Beethoven for the rest of his life. In fact Ludwig van Beethoven is to be considered the last and fines representative of the Mannheim School – though even during his early lifetime the importance and influence of the school in Europe was already going weak.

With this spiritual background and his unshakable faith in his calling and talents, he was going to go to Vienna not to be a wing-man, a second violin, a runner up, but the one to beat and raise above even the heavy weights of the time: Haydn and Mozart!

Upon arriving in Vienna with some serious recommendation letters, especially from Count Waldstein, he first found a room to rent, bought a new set of clothing and an entry level piano. He was financially supported by the Elector of Bonn with the condition to learn music from Haydn – and one day return to his Court.

There never was a better time for a musician to be in Vienna! The city was full of professional and amateur musicians, the population was hungry for music. Music then was a limited commodity, unlike today, when listeners can buy, stream, download music and carry them even on their phone. If a Viennese wanted to hear music, had to attend a live concert at a wealthy friend’s or buy the score and play it him-, or herself.

In this vibrant atmosphere Beethoven had taken root quickly. Being a piano virtuoso, surpassing even Mozart in improvisation and technique, he was a celebrated guest among Viennese aristocracy. In this era, when feelings became fashionable in arts, this young man could make the audience cry, whenever he wanted to. He even participated in piano contests, where a short random theme had to be taken and developed into a long improvisation. No one stood the ground against him!

Being the student of Haydn was to be considered a great honor. Joseph Haydn was a musician superstar all over Europe, so much so, that contemporary British newspapers were openly proposing a plan to kidnap Haydn from Esterháza and bringing him to London – thus giving him the freedom he deserves. He was no prisoner, of course, but a loyal person to Prince Nikolaus Esterházy, serving him almost 30 years.

The young and arrogant Beethoven was not impressed, he – unfairly – said “learns nothing from Haydn”. He parallel started taking lessons from Johann Georg Albrechtsberger, who was the organist at St.Stephen Cathedral; and also from Antonio Salieri, the imperial Kappellmeister. As the French had occupied Bonn (and the Elector fled), Hayden decided to go to London again in 1795, unexpectedly the student-era came to an end. Beethoven would not return to Bonn, but became independent for the first time in his life.

1795 marked his first public concert, where he played his Piano concerto No.2 (opus 19). Subsequently, he published the Three piano trios, which was his first work with opus number, opus 1 (dedicated to Prince Lichnowsky). This also marked his first notable financial success, covering his living for more-or-less, a year. In the next three years he occasionally traveled for concert tours from Berlin to Prague. As the new millennial drew closer, after the first period, it was time for a new chapter: his middle period.

Music of the middle period – the World blown away

Some consider the beginning of the middle period starting from 1802, the birth of the Heilgenstadt Testament. In this letter – intended to his brothers – Beethoven finally sheds light on the reasons of his withdrawal from society: his permanent and progressive illness in his ears. In this testament he reveals the desperation and sorrow he faces on daily basis, even considering ending of his life. He concludes the letter by a strong commitment to live on in order to share the music he feels inside with humanity.

By this act he becomes the Messianic figure of music, a human being who devotes his whole and complete life to music, in order to serve humanity. This newly found calling and bursting energy makes the next decade unequaled in terms of productivity and quality. Under this evil time pressure – fearing the fast approaching deafness – he frees himself from the stylistic boundaries of the 18th-century, creating something very new and changing music forever. Beethoven said, “I am not satisfied with the work I have done so far. From now on I intend to take a new way.” This new way is also called his heroic phase.

The first and most important milestone in this new way was the Third Symphony, also known as the Eroica (heroic). This work was larger in scope, longer in time and more difficult to comprehend than any other symphony the world has ever seen until then! In fact this was the first musical work that required the audience to hear it more times, even studying the score to grasp the richness of it. Just the first movement alone is longer than any of the symphonies that were written by Haydn or Mozart.

Without aiming for completeness here, the middle period gave the world the symphonies from III-VIII., the Emperor concerto (surpassing Mozart’s piano concertos), five string quartets, Violin concerto (op.61), many piano trios, including the Archduke Trio, piano sonatas like the Waldstein, Apassionata or Beethoven’s only opera, the Fideilo.

Fate knocking – the loss of hearing

One day in 1798 Beethoven had a visitor. After showing him to the door he sat down at his piano to continue composing. A bit later there was a knock at the door. The composer got very angry for interrupting him, jumped up to rush to the door. As he took a step, fall over his chair with face to the ground. Immediately his ears started to buzz.

This was the day and the time from which Beethoven originated his struggle with his ears. There were periods, when his hearing got better, but never recover. Gradually, he would lose his hearing, first the higher notes, then by 1814 completely.

There are many theories concerning the reason of this illness, some are more comic than scientific. This magazine chooses to believe that Beethoven had a Paget’s disease (abnormal bone regeneration in the skull resulting bones thicker than normal) and there was nothing to be done by and with contemporary doctors or medical science.

As the loss of hearing advanced Beethoven started to ignore social interactions. He considered it a great shame for a musician and assumed that his reputation would suffer if truth got out. His days as piano virtuoso were numbered. More and more often public concerts as a pianist were compromised by his failing hearing. There is uncertainty concerning Beethoven’s last concert, by some sources it was in 1811 with the Emperor concerto (no.5), others claim it was 1814, the Archduke Trio.

As communication became more and more difficult he introduced a conversation book, where people could write a question and he would answer orally. Approximately 400 such books exited, many allegedly destroyed later by his secretary, Anton Schindler.

Immortal Beloved

Beethoven’s love life was a disaster. He constantly fell in love with his piano students, often dedicating them compositions, but he was fishing in the wrong pond. The laws of aristocracy allowed the marriage between classes, but a noble woman marrying with a commoner would result in losing her title forever. Although, many was in love with Beethoven, often rather with the genius than the real man, no one was devoted enough to give up the title for love. Thus, at the end of all these loves, heartbreak awaited Beethoven.

Among the many, some stand out as more serious relationships. In 1801 countess Giulietta Guicciardi, to whom the Moonlight sonata (Op. 27) was dedicated. Josephine Brunsvik, another pupil who at the end refused him, partly because of the pressure from her family. Around 1810 another dedication the Für Elise to Therese Malfatti, which is yet another love that did not come to fruition.

Finally, the most important one the Immortal Beloved. After Beethoven’s death a letter was found among his personal belongings. This is a 10 small pages long love letter, without date, place and any name or indication who the addressee might be. The analysis of the letter is going on for almost 200 years without any final conclusion. What is certain is that the letter was written in summer 1812, at the spa town of Teplitz. In 1972 Maynard Solomon published a book in which – after some serious detective work – he names Antonie Brentano as the Beloved. This work is to be considered the most comprehensive in the subject and thus the conclusion is the most likely solution.

There are two schools concerning Beethoven’s sexual life. One school believes Beethoven died as a virgin, simply because his strong and high moral values would not allow sexual affairs. The other group is convinced he was a regular guest at brothels, something that made him deeply divided. The second group has a strong support from one of Beethoven’s letters, in which he confesses that such experiences make his body satisfied, but his soul disgusted.

Regardless which school is right, it is a sad fact that all his life it was only his mother, the only woman from whom Beethoven received full acceptance and love.

Patronage – a controversy

Having an early baptism in the ideas of enlightenment Beethoven had an ambivalent relationship with the nobility. On one hand he strongly despised the aristocracy and the idea of having a social hierarchy based on birth and family rights. There is this famous letter from 1808 he wrote to one of his friends and early patrons, Prince Lichnowsky, who tried to force – and presumably threatened – him to play in front of his French soldier guests. The two had a very nasty row, Beethoven leaving the house in rainy weather and never forgiving him (raindrops still visible today on the original Appassionata score, on which he was working during his stay). The letter says “Prince, what you are, you are through chance and birth; what I am, I am through my own labor. There are many princes and there will continue to be thousands more, but there is only one Beethoven.” This quote shows faithfully how he was thinking about birth right privileges.

On the other hand, Beethoven was the musician of connoisseurs, like it or not, the aristocracy of that time. He also depended financially on these patrons. He gave them private performances, many compositions were commissioned by them. Such important patrons were Prince Lobkowitz, Count Razumovsky and the most important Archduke Rudolph, the youngest son of Emperor Leopold II.

Beethoven was always anxious concerning his daily bread, thus in 1808 he decided to accept the invitation from Napoleon’s brother Jérôme Bonaparte, king of Westphalia, to be his Kapellmeister at the court in Cassel. This would have been a well paid and stable position. Upon hearing the news, Archduke Rudolph, Prince Lobkowitz and Prince Kinsky begged him to stay in Vienna and for exchange they pledged to pay him a yearly 4 000 florins. Personal tragedies, inflation and the war with France finally eroded this income source with no new patronage coming forward.

Beethoven and his nephew

This episode of Beethoven’s life is by far the most disturbing. Stepping in his father’s shoes so early, being guardian of his brothers and the breadwinner of the house, made him a very protective and intruding big brother. Apart from the physical well being he was evenly interested in their moral acts.

His brother, Kaspar had been very ill in 1815 and despite Beethoven’s efforts paying and bringing good doctors to attend him, he died from tuberculosis (just as their mother). In his deathbed giving in to the pressure from his brother, he signed a will and in it giving sole custody of his 9 years old son Karl, to Beethoven. Johanna, his wife and the mother, upon realizing this act, begged to his husband to change it, which he did to shared custody. Beethoven would have none of it! He absolutely opposed this marriage in the first place, seeing Johanna as morally unfit for the family and parenthood, calling her the queen of the night (she later had an illegitimate child and also was convicted of theft). After Kaspar’s death a 5 years long bitter custody battle started that eventually had devastating results for all of them.

Beethoven was first awarded sole guardianship on the Landrechte (court for the nobility), but later as it became clear that the ‘van’ in his name has nothing to do with German nobility’s ‘von’, his case was transferred to the commoner’s civil court, where he lost. This revelation alone was a big blow to him, as until that day Vienna was convinced, he was a noble. Beethoven appealed and regained sole guardianship again. As a last desperate attempt, Johanna made an appeal to the Emperor himself, who decided not to interfere in the case.

Karl was confused emotionally, not only loosing a father, but being in the middle of a custody battle. Beethoven forbade him to see his mother, but the boy frequently disobeyed him and run away – even skipping school – to be with her. Although Beethoven did everything to raise the child the best possible way, Karl grew up unhappy.

From this agony, being trapped in his uncle’s overbearing love, he finds only one way out. He buys a pistol, climbs to the Rauhenstein ruins and attempts suicide. He misses first, with the second he fractures his temple. When he is found, he asks to be taken to his mother. The failure of Beethoven as a father was complete.

After recovery, Karl leaves on the 2 of January, 1827 to join the army. He would never see his uncle again.

In this very sad story all actors lose. Beethoven lost his reputation in Vienna, the public considering him a monster and a madman. Johanna lost a child and lived with a mudded reputation all her life. Karl, his life and personality wounded forever. Finally, the audience, who lost a lot of unborn compositions, as Beethoven would not write a single note for years, during this emotionally draining period.

Karl was the only child from the three Beethoven sons. Two generations later, the already American born Karl Julius van Beethoven died without a son, thus the Beethoven name died out.

The last years

Just as the legal battles over Karl began to settle Beethoven entered his third and final phase of his creative life. As productivity compared to his previous periods had declined, a new even more refined creative energy emerged through his hands. The two main influences on this new direction is his increasing and slowly complete deafness; and the rediscovery of the works of J.S.Bach and Handel.

As his hearing loss became complete his boundaries from the physical world disappeared. There was no longer any feedback coming from the hearing, just the limitless imagination. Losing this sense also made him more focused and meticulous in his writing.

In his social life he became even more withdrawn. Communication was possible only through conversation books. In these the questions were written down and he would answer them orally. He also became somewhat more content with his household keep, Nanette Streicher managed to tame the beast and continued to provide for him even in his illnesses.

From 1818 he began to work on important works such as the Hammerklavier Sonata (op. 106), the Missa Solemnis (op. 123) and Diabelli Variations (op. 120). A long time desire to put Friedrich Schiller’s poem the Ode to joy into music, also started to shape in the form of the epic Ninth symphony. A former student Ferdinand Ries, who settled in London and became a founder member of the Philharmonic Society of London, raised interest in the works of Beethoven. Although the Ninth was premiered in Vienna (1824) and the printed edition was dedicated to Frederick William III, king of Prussia, the London Society has a hand written first movement dedicated to them by Beethoven. The public opinion considers the Ninth to be commissioned by London.

As archduke Rudolf was to become archbishop of Olmütz in 1820, Beethoven began to work on Missa Solemnis for the installation ceremony. The piece was not finished in time (1820), in fact not until three years later that the complete manuscript was sent to the archbishop. This composition is considered by many the most important religious work ever written in the history of music.

In 1824 the Ninth was premiered in Vienna in the Kärntnertor Theatre. Beethoven himself supervised the preparations and was sitting next to the conductor during the performance. Being unaware of the applause at the end it was the soloist who made him turn and face the audience. He was hailed five times in the age, when the Emperor usually received three! This was his last work for large scale orchestra.

His final commission came from the Russian prince Nikolai Galitzin, who asked for three string quartets. These became part of the Late Quartets, music that was so difficult, labeled unplayable by the musicians and incomprehensible for the audience. The Fourteenth Quartet (op. 131) was Beethoven’s favorite, which he considered his most perfect work. This was dedicated to baron von Stutterheim, the military officer who took care of Karl in the army.

The end

Beethoven was born in a body that was the complete opposite of his music. Most woman considered him ugly, short and shabby. His face was scarred from smallpox he had contracted in his childhood. His entrails were giving him constant inconveniences and suffering in the form of vomiting and diarrhea . Once he almost lost a finger due to infection. His liver was under stress due to his (sometimes heavy) drinking. Apart from these specifics he was often stricken with all kinds of sicknesses. His last months and days were spent in serious illness and in bed.

Beethoven spent the summer of 1826 with Karl at his only remaining brother’s estate, Nikolaus Johann. It was after the suicide attempt of Karl, and his uncle decided that the countryside will have good effect on the young man. As months passed Johann suggested to Beethoven that it would be beneficial for young Karl to do something useful already, as idle time will not heal him any further. Beethoven, as usual, reacted in an overheated, emotional way jumping on an open coach (!) leaving right away without proper winter clothing. During the journey he contracted a pneumonia, which was a fatal blow to his body’s immune system and finally lead to his death months later.

On his deathbed doctors conducted four operations addressing his abdominal swelling, from one of them an infection developed. Soon, it was clear that he would not recover and the end is near. His last recorded words were Pity-pity – it is too late! – as he was told a publisher sent him twelve bottles of wine.

It is not possible to know what exactly happened during his final hours, there are many different reports of the events. What seems to be exact is that his friend Anselm Hüttenbrenner and a woman was present. Some reports say it was Johanna van Beethoven, his old despised enemy, which seems to be unlikely. The woman must have been Sali, his maid. It was the end of March, weather still cold and a thunderstorm was gathering above Vienna. Legend has it that after an awful thunder the dying man raised his head, stretched his right arm and shook with anger, then fall back and was dead.

Ludwig van Beethoven died in his Schwarzspanierhaus apartment in Vienna, 26 March 1827. He died at the age of 56.

The autopsy performed by Dr. Johann Wagner the next day revealed liver disease. A shrunken liver could be the result of alcoholism, but also Hepatitis A, which was common in the 19th century. Analysis later showed significant amount of lead in his hair, which may be the direct consequence of cheap wine consumption, that was commonly sweetened with lead sugar, despite being banned all over Europe.

The funeral was held on 29 of March and an estimated 20 000 people attended. First, he was buried in Wahring cemetery, but in 1888 his remains were moved to Vienna’s Zentralfriedhof, where he remains even today.