These days we celebrate Passover and Easter, and it can be a good opportunity to look beyond the chocolate bunnies and painted eggs, and reflect at least on one aspect of these events: the story of human nature. In the Passover story we celebrate the freedom regained after 400 years of cruel slavery, in Easter’s Passion story we remember the rejection and crucifixion of “The Good”. None of the stories tells of human goodness.

Today, many societies aim to raise children into adults believing we are unique snowflakes: special, good as we are, destined to change the world with our one-of-a-kind brilliance. Parents, teachers, and inspirational quotes on coffee mugs tell us we are meant to shine. But, instead of a generation of bold trailblazers, we have ended up with a crowd of egoists whose self-esteem wobbles like a house of cards when their latte is not Instagram-worthy. Turns out, being “special” mostly means we are uniquely sensitive about ourselves, ready to crumble when the world does not agree with or applaud our every move. In such an environment the idea that human nature is inherently flawed and we have work to do on ourselves, is unthinkable.

In this article, by weaving together biblical teachings, the insights of ancient Greek and Roman philosophers, historical evidence and contemporary observations, we try to make the case that human nature and conscience in itself is not able to reliably function as a good entity.

The biblical view

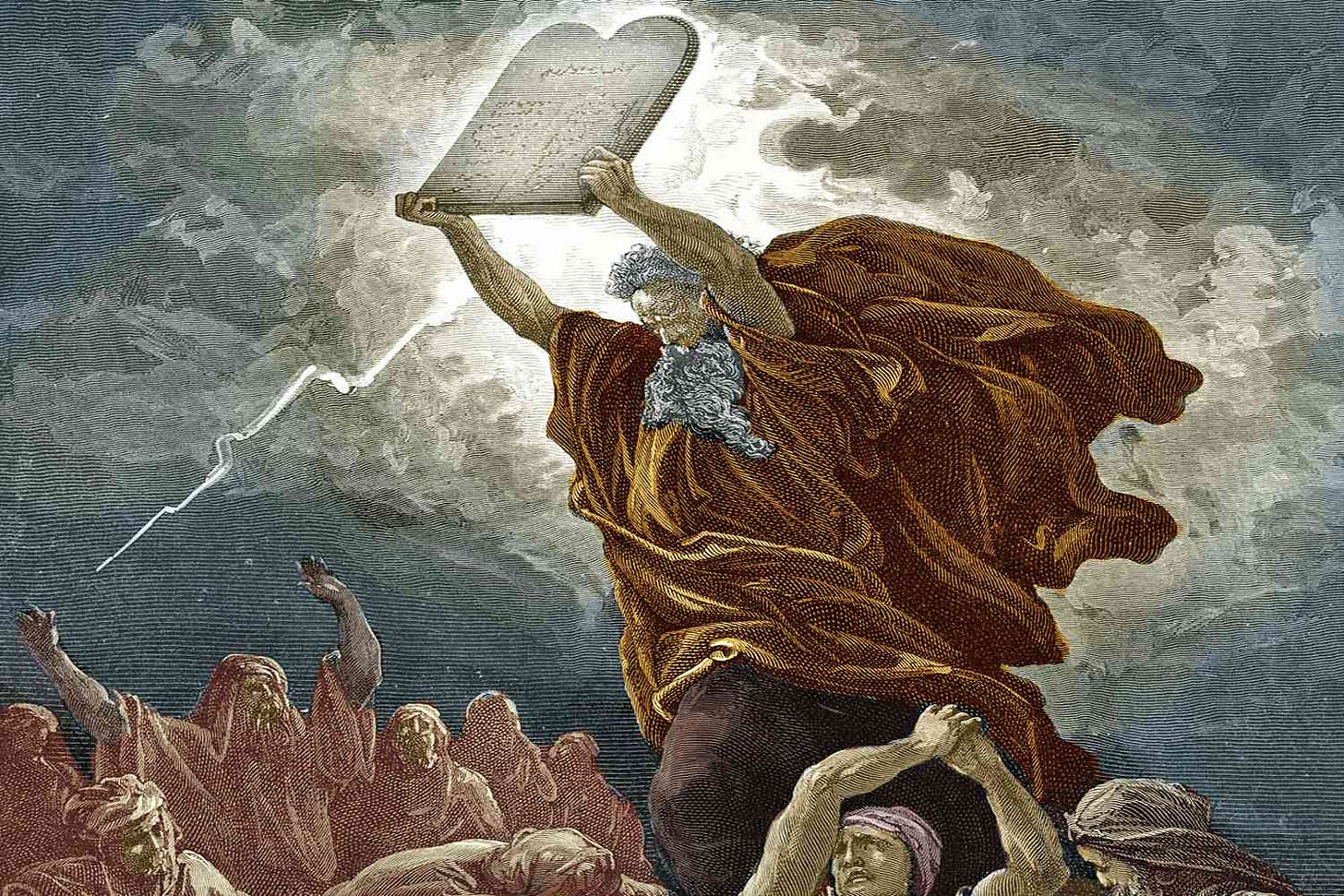

The Torah (the 5 books of Moses), in Genesis 8:21, declares, “every inclination of the human heart is evil from childhood.” This stark pronouncement sets the tone for a biblical worldview that sees humanity as inherently flawed, leaning to selfishness, and in need of divine guidance. The Bible does not romanticize human nature, rather it presents it as a battleground where evil inclinations must be constantly checked by adherence to God’s commandments. This perspective resonates in the writings of ancient Greek and Roman philosophers, who, while not bound by biblical theology, similarly questioned the innate goodness of humanity.

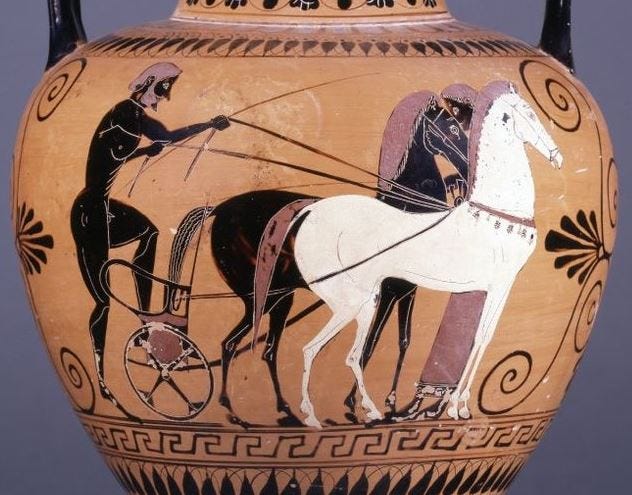

Plato, in his Republic, argues that human beings are driven by appetites and desires that, if left unchecked, lead to chaos and injustice. He likens the soul to a chariot pulled by two horses, one representing reason, the other base desires, requiring a skilled charioteer to maintain balance. Without such discipline, Plato warns, humans succumb to their baser instincts, a view that aligns with the biblical assertion of inherent evil tendencies.

Similarly, Aristotle, in his Nicomachean Ethics, emphasizes that virtue is not innate but cultivated through habit and education. He writes, “We become just by doing just acts, temperate by doing temperate acts,” suggesting that goodness is an achievement, not a birthright. These classical perspectives bolster the biblical rejection of inherent goodness, highlighting the necessity of deliberate effort to overcome natural inclinations toward vice.

Historical evidence

History provides a long and grim list of evidence against the notion of human goodness. The Roman Coliseum, with its spectacles of men (and often women) fighting to the death, and prisoners devoured by wild beasts, stands as a testament to humanity’s capacity for cruelty. Wars across centuries have been marked by mass killing, torture, rape and slavery, which further underscores the barbarity embedded in human behavior. The 20th century alone witnessed atrocities of unparalleled scale: the Holocaust’s systematic extermination of millions, Stalin’s purges, Mao’s famines, the Cambodian and Rwandan genocides, and Japanese war crimes, including the exploitation of comfort women and unethical medical experiments on humans.

In light of such horrors, to believe in humanity’s basic goodness is to engage in irrational thinking. The Stoic philosopher Seneca, reflecting on human vice, wrote, “We are all wicked. What we condemn in another, each of us finds in himself.” His observation echoes the biblical view, urging introspection rather than denial of our flawed nature. Cicero, another Roman thinker, argued in De Officiis that human beings are capable of great virtue but only through adherence to moral duties grounded in reason and justice, not through an assumed goodness.

Daily observations

Beyond history, everyday life challenges the idea of inherent goodness. Parents must repeatedly instruct children to say “thank you” or share with others, suggesting that politeness and generosity are not instinctive but learned. If humans were naturally good, a single reminder would suffice. Instead, behaviors like bullying and abuse among children reveal cruelty that requires correction. Proverbs 22:6 says: “Train up a child in the way he should go, and when he is old he will not depart from it.”

Plato’s emphasis on education as a means to shape the soul complements this view. He argues in Laws that without proper upbringing, humans revert to their natural selfishness. Similarly, the Stoic Epictetus taught that moral progress depends on disciplining one’s desires and actions, stating, You have to practice day by day to control yourself. These philosophical insights underscore the biblical insistence on moral instruction, revealing the folly of assuming goodness without effort.

Things we consider normal today….

Living in societies shaped by biblical, Judeo-Christian values can create a false sense of human goodness. In nations where decency prevails, some naively attribute this to human nature rather than the moral framework that underpins it. Things we consider today as social norms (or law) were not evident two thousand years ago, and a new, outsider and unifying ideology had to come in order to change. My favorite example to support my statement is the history of the conversion of the German tribes.

The German barbarian tribes of the early centuries, such as the Goths and Vandals, resisted Christianity not for theological reasons but because their warrior culture glorified violence and conquest, which clashed with Christian teachings. These tribes thrived on raiding and warfare, viewing killing as a path to honor and power. They had a similar approach to abduction and raping women or stealing from rival tribes. It is fair to state that this moral standing was not unique to the German tribes, but in fact was the general norm for all other pre-Christian tribes in Europe. Today, if a person acts like this, they are apprehended by the police and face justice.

Aristotle’s concept of the polis as a community that cultivates virtue through shared laws and values aligns with this observation, suggesting that goodness is a product of deliberate societal structures, not an inherent trait.

The case against naivety

The belief in human goodness is not merely misguided, it is dangerous. For example, by assuming children are naturally good, parents and educators neglect the critical task of character education, prioritizing self-esteem over self-control. This leads to generations ill-equipped to wage the “inner battle” against negative traits like selfishness, laziness, and evil.

Furthermore, this belief undermines the necessity of a transcendent moral source. If humans are inherently good, who needs God or the Bible? Yet, as Plato argues, true morality requires a standard beyond human opinion, a divine anchor like the one that the Bible provides through the Ten Commandments. Without such a framework, societies risk moral relativism, where evil is excused as a product of external forces like poverty or racism. The tendency to blame society rather than individuals for evil is a direct consequence of believing in human goodness.

The true source of evil lies in a malfunctioning conscience, a missing and/or defective value system, or lack of impulse control. The solution, as the Bible and classical philosophy suggest, is a combination of good values, just laws, and a God who commands goodness.

Seneca urges individuals to confront their flaws when he says, “To be good, you must first believe you are bad”. The most critical question for any family and society, then, is: “How do we make good people?” The answer lies in divine guidance, moral education, and the relentless pursuit of self-discipline, as both the Bible and thinkers like Aristotle and Epictetus affirm.

Listen to an extended audio conversation on this topic on Popular Beethoven’s YouTube channel – supported by AI!