The Emperor represents the composer at the peak of his “Heroic” style, creating music of unparalleled scale, power, and emotional resonance.

Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 5 in E-flat Major, Opus 73, famously known as the “Emperor” Concerto, is not just music. It is a bold statement: heroic, innovative, and deeply expressive. It represents a pinnacle of the Classical concerto form at the same time pushing its boundaries, paving the way for the Romantic era.

The setting

To truly appreciate the “Emperor,” we need to understand the context in which it was born. Beethoven composed it primarily in 1809 in Vienna. This was not a peaceful time. Napoleon’s French army was marching across Europe, and in May 1809, they besieged, bombarded, and eventually occupied Vienna.

Cannon fire echoing through the streets, uncertainty and fear everywhere. Beethoven, already struggling with his increasing deafness, was caught in the middle of this chaos. During the heaviest bombardments, he sought refuge in his brother Kaspar’s cellar, covering his tormented ears with pillows to protect what little hearing he had left and to shield himself from the terror.

Despite these conditions, or perhaps fueled by them, Beethoven created a work of extraordinary power and grandeur. This period marks the height of Beethoven’s “Heroic” middle period, a time characterized by works of unprecedented scale, emotional depth, and revolutionary spirit (like the “Eroica” Symphony No. 3 and his Symphony No. 5). The Piano Concerto No. 5 fits perfectly within this creative period.

Why Emperor?

One of the most often asked questions is about its nickname, Emperor. It certainly sounds imperial, majestic. However, Beethoven himself did not give it this title. In fact, given his complex and ultimately disillusioned relationship with Napoleon (whom he initially admired as a revolutionary hero but later despised for crowning himself Emperor, famously scratching out the dedication to him on the “Eroica” Symphony), it is highly unlikely Beethoven would have given this name.

The most widely accepted story attributes the name to Johann Baptist Cranz, a German pianist, composer, and publisher who was an early admirer of the work. Reportedly, upon hearing the concerto’s character, Cranz or possibly a French soldier during the Vienna premiere exclaimed, “C’est l’Empereur!” (“It is the Emperor!”). Whether this specific incident is true or not, the nickname stuck, likely because it so well captures the music’s noble essence. It evokes images of triumph, ceremony, and authority.

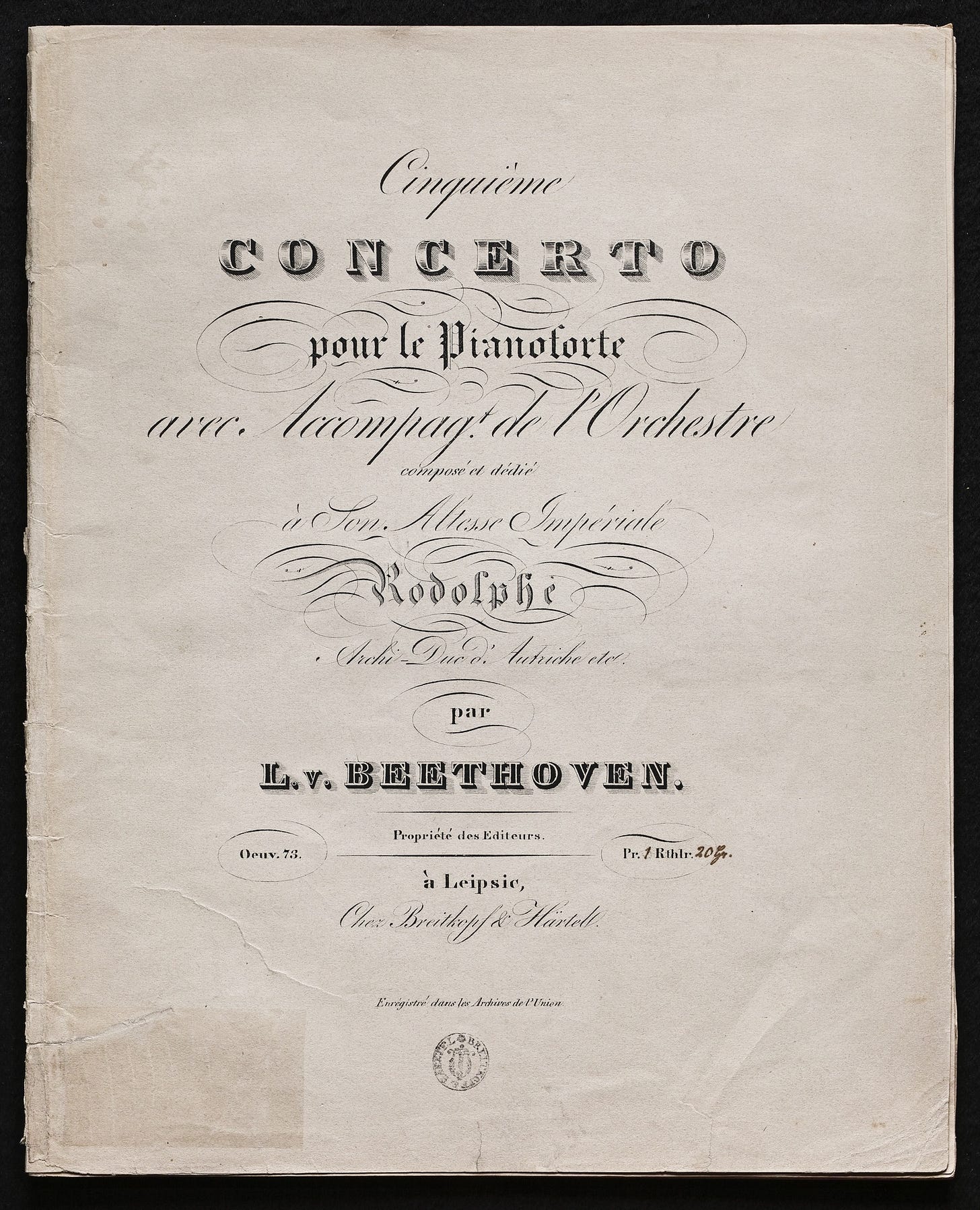

The concerto was dedicated to Archduke Rudolf of Austria, Beethoven’s patron, friend, and student.

A groundbreaking masterpiece

The “Emperor” Concerto follows the traditional three-movement structure typical of Classical concertos, but Beethoven spices each movement with innovation.

Movement I: Allegro (E-flat Major)

The concerto opens with a bang, literally. Instead of the usual long orchestral introduction, Beethoven starts with a dramatic chord, followed by a dazzling piano work. This bold opening was shocking for its time, breaking tradition.

The first movement is in sonata form, a structure like a musical argument with two main themes. The first theme is majestic, with a march-like rhythm that feels regal. The second theme is softer, almost singing, offering a moment of calm. These themes twist and turn, with the piano and orchestra tossing ideas back and forth.

What makes this movement special is its energy. It is like a conversation between a strong leader (the piano) and a dedicated team (the orchestra). Beethoven fills it with surprises, like sudden quiet moments or explosive bursts, keeping listeners on edge of their seats. It lasts about 20 minutes, the longest of the three movements, and feels epic indeed.

Movement II: Adagio un poco mosso (B Major)

After the first movement’s fireworks, the second movement is a significant contrast. It is slow, tender, and introspective. The orchestra sets a hushed mood with muted strings playing a simple, hymn-like melody. The piano enters gently, spinning delicate variations on this theme.

It’s short – around 7-8 minutes -but its beauty lies in its simplicity.

Movement III: Rondo: Allegro ma non troppo (E-flat Major)

The finale bursts in with a lively rondo, a form where a catchy main theme keeps returning, like a refrain in a song. The piano starts with a bouncy, joyful melody. The orchestra joins in, and the music dances through contrasting episodes – some playful, some stormy – before circling back to that main theme. This movement is pure celebration. Near the end, there is a defining moment where the timpani (kettle drums) rumble softly, building tension, before the piano and orchestra race to a loud finish.

Beethoven’s deafness and the premiere

By the time the “Emperor” Concerto was ready for its public premiere, Beethoven’s deafness was so advanced that he could no longer trust himself to perform as the soloist in a major public concert, especially for a work of this complexity. His last public appearance as a pianist had been in 1808 and even that was a disaster.

Therefore, unlike his first four piano concertos, Beethoven did not premiere the Fifth himself. The honor of the public premiere went to the pianist Friedrich Schneider in Leipzig on November 28, 1811, conducted by Johann Philipp Christian Schulz. It was very well-received there.

The Vienna premiere took place a few months later, on February 12, 1812, with Beethoven’s student Carl Czerny (who later became a famous piano teacher himself) as the soloist. Reports from the Vienna premiere are mixed. While some recognized the work’s genius, others found it too long, too unconventional, or even chaotic. Composer Ignaz Moscheles attended and was deeply impressed, but the general audience reaction seems to have been less enthusiastic than in Leipzig.

Legacy and enduring appeal

Despite any initial mixed reactions in Vienna, the “Emperor” Concerto quickly established itself as a cornerstone of the repertoire. Why does it remain so overwhelmingly popular today, performed countless times in concert halls and featuring on numerous recordings? Here are some answers

- Musical power: The music itself is incredibly compelling, from the electrifying opening to the sublime slow movement and the joyful finale, it grips the listener.

- Heroic spirit: Its bold, confident, and ultimately triumphant character resonates deeply. It feels like a victory snatched from the jaws of adversity, reflecting perhaps Beethoven’s own struggles.

- Balance of virtuosity and expression: While incredibly demanding for the pianist, the virtuosity always serves the musical expression. It is not just flashy, it is meaningful.

- Emotional range: The concerto covers a vast emotional landscape: grandeur, tenderness, struggle, joy, introspection, and triumph.

- Accessibility: Despite its complexity and depth, the main themes are memorable, and its overall musical narrative is relatively easy to follow, making it accessible even to those new to classical music.

The “Emperor” Concerto is more than just Beethoven’s final piano concerto. It is arguably the culmination of the Classical concerto tradition and a bold leap into the future. The “Emperor” was among the first concertos to treat the piano like a symphonic instrument, paving the way for Romantic composers like Brahms and Tchaikovsky, whose concertos owe a debt to Beethoven’s vision.

It represents the composer at the peak of his “Heroic” style, creating music of unparalleled scale, power, and emotional resonance. It stands as a towering achievement, a work that continues to inspire awe and move audiences centuries after it was written – truly an emperor among concertos!

Listen to Beethoven’s Emperor Concerto here on YouTube!

Listen to an extended audio conversation on Beethoven’s Emperor Concerto, on Popular Beethoven’s YouTube channel – supported by AI!