A conversation about understanding music, Beethoven’s Große Fuge, and musical animation.

American composer, pianist and software engineer, Stephen Malinowski, is best known for his musical animations, nicknamed Music Animation Machine.

His visual representations help to understand the different textures in a piece of music, that is, the different layers of sound, and the relationship between them. They are colourful and interesting to follow, and are especially useful in guiding us through unusual and complex pieces.

Malinowski explains that through visualisation, our brains can comprehend multiple things at once. Taking advantage of this, our eyes lead our ears through the music!

In 2012, Malinowski developed a version of the software that could synchronize his animations with realtime performances. He showcases this at the TEDx conference with violinist, Etienne Abelin and pianist, Dorothy Yeung playing Bach:

We asked Stephen to share with us some insights into his fascinating musical career, starting with his recent work on Beethoven’s Große Fuge, a piece that is particularly difficult to follow:

The Große Fuge is an especially demanding piece for many listeners. How does your animated score help us understand Beethoven’s most complex work?

Beethoven wrote different pieces with different audiences in mind. His symphonies were written for what today might be called “the general public,” and are his most accessible large-scale works.

His chamber music was intended for a more select audience—those able to attend (and appreciate) chamber music performances (or play it for their own enjoyment).

His piano music is a mixed bag; some pieces are relatively easy, and were composed for amateurs, some were his experiments (this is especially true of the bagatelles, which often contain elements that appear in other music he wrote around the same time), and some were his most difficult, esoteric, profound creations.

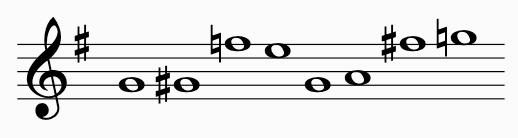

The Große Fuge may not be his most esoteric piece, but it is certainly one of the most difficult, for both performers and listeners. The difficulties start with its main subject …

…which is angular, disjoint, and highly chromatic—making it both hard to follow as a continuous melody and hard to understand harmonically even if you can follow it melodically. The countersubject (introduced at the start of the fugue) is also very angular …

The interaction between these subjects (and material derived from them) results in a musical texture that’s very hard to parse: it’s hard to follow the voices because they’re so disconnected, and the harmony is highly chromatic, so it’s hard to hear the chord progressions.

The difficulty is compounded by the fugue’s highly syncopated rhythm. This starts from the opening of the fugue …

… where the second note of the countersubject sounds like a downbeat, and this (incorrect) interpretation is reinforced by the entrance of the main subject when the countersubject’s pattern repeats. The syncopation persists until the cadence on the downbeat of measure 47, half a minute after the fugue’s start (in measure 30)—a long time to go without any unambiguous harmonic or rhythmic signposts.

And the difficulties don’t stop there. Through the piece, the main subject is played in various rhythms, at various speeds, broken up into fragments. This is clearly not music for beginning listeners!

The most important thing I’ve done to make it easier to follow the piece’s logic is to present the main subject with the same graphical elements, regardless of how much manipulation it’s been subjected to. Because of this, the subject’s notes move slowly when it’s being played slowly and whisk by when they’re fast.

The second most important thing is that the four instruments of the quartet are identified by color, so that when the texture gets complicated, it’s possible to follow an angular, disjoined line by eye.

Finally, to help make the piece make sense as a whole, I’ve identified the other material (other than the main subject and countersubject) with shapes and the manner in which they move:

In your work on the Große Fuge, you give the interesting example of Snooky the cat becoming startled at every tick of the metronome. The cat does not recognise the pattern therefore each tick is unexpected and makes it jump. Could you explain to our readers why you used this example in relation to musical learning and understanding?

On my Understanding Beethoven’s Große Fuge page, I was trying to correct a common misapprehension about musical listening: that a given piece of music sounds the same to all listeners.

People who say the Große Fuge is (to quote from composer Louis Spohr) “an indecipherable, uncorrected horror” think that they’re having the same experience as every other listener, and that those who say they like the piece just have bad taste, or bad judgement, or are deluded or deranged in some way (or just lying).

Some aspects of musical listening are innate and shared among all listeners, but these are pretty basic—are analogous to an infant being able to understand the emotional content of its mother’s voice. But, as with spoken language, the meaning of music is learned over years of exposure and experience. For people living in a particular musical environment (e.g. the United States in the 21st century), certain core elements of musical understanding, a basic vocabulary, are shared, but that’s just a starting point. Every musical genre has its own specialized way of doing things, and some of these are complicated enough to be incomprehensible to the uninitiated. The Große Fuge has some of that.

The fact that a piece of music can be meaningful to one listener and meaningless to another can be hard to believe at first, especially if you’ve lived your life with people in a shared musical environment. To overcome this, I assembled a sequence of demonstration examples and training exercises.

The Snooky the cat video shows how it’s possible to not understand a sound.

Snooky doesn’t not understand the sound of the metronome. By “understand” I mean that Snooky doesn’t have enough of an idea about when the next click will happen to not be surprised by it.

Snooky doesn’t understand rhythm. The click of a metronome is very easy for humans to understand (we know exactly when the next tick is coming), and we can understand much more complicated rhythms, too.

The point of the Snooky video is that Snooky does not understand the metronome the same way we do. But maybe it “sounds the same” to Snooky as to us?

To demonstrate that it’s possible to hear the same exact sound in different ways, I used the “Hearing sounds as speech” examples (learn more here), in which it’s possible to hear a sound and not understand it, and then hear it again, and be able to—a change that’s due to experience/learning.

But even with the “Hearing sounds as speech” example, it’s possible to feel that “it still sounds the same.” To overcome that objection, I presented the “Hearing speech as music” example, in which something that is initially perceived as “not music” can be learned to be heard as music.

The final step is to provide something to help people learn how to hear what’s going on in the Große Fuge—training wheels for the ears. First, for rhythm. As I mentioned, the piece is so highly syncopated that it’s hard to tell where the beats are.

In this video, I’ve marked the downbeats of each measure with a bouncing arc:

In the opening Overture, the harmonies underlying the subject are hard to infer, and in the fugue proper, the angularity of the countersubject gets in the way of hearing the chords, so I’ve made this simplified version of the beginning of the piece in which the texture is simplified and the harmony is filled out to make it more obvious:

My hope is that if a listener learns to hear what’s going on in the simplified version, they’ll be in a better position to start learning how to hear Beethoven’s version.

The beginning of the Große Fuge is much harder to understand than the later parts, but many listeners give up after a few minutes. Hopefully, these tools can help.

Your YouTube channel has a wealth of videos for our readers to familiarize themselves with your work. Is there one that is particularly dear to you?

So far, I’ve published over two thousand animated graphical scores on YouTube. I’m guessing that most of them I’ll never have an opportunity to think about again. When I go back and watch my videos, I sometimes think “I could do a much better job than this,” and I sometimes think “I really like this,” but it never translates to “this is one of my favorites.” This is probably at least in part because I have such a bad memory (and only getting worse now that I’m moving into old age) that I don’t remember the videos one way or the other. I know this because when I watch videos from more than a few months ago, it’s almost as if somebody else had made them, and I only remember what’s in them a few seconds before it happens. What does happen sometimes is that I’m talking to someone, and I’m reminded of a video I’ve made that I want to recommend to them. In that case, I typically add it to this page:

I haven’t counted, but that page probably lists about a tenth of the videos I’ve made, and the ones I’ve selected have to have been exceptional in some way, so it’s probably the best place to start if you’re interested in finding “the good stuff” (which is different for every person).

From a young age, you have played an enviable array of musical instruments including the recorder, guitar, piano and viola. What role does playing music have in your life currently?

These days, I spend almost all my time making videos. I sometimes play the music in those videos on the piano (as part of learning about it), and I sometimes play other pieces on the piano (or organ) for pleasure, but I’m not playing music nearly as much as I did in the first half of my life.

Which professional achievement are you most proud of in your musical career?

I don’t think I’m particularly proud of any of my achievements. The things I’ve learned are things that lots of people have learned, and the ideas I’ve had are just ones that would be obvious to most people in my situation (I know this because viewers often comment “you ought to try _____” for things that I have in fact already tried).

I’m not highly motivated, so what I’ve done is just the result of doing whatever I felt most like doing. I’m not ambitious enough to attempt things that are hard for me.

The way I look at it is that I’m lucky to have had experiences and learned things that, over time, added up to the ability and desire to make animated graphical scores, and that there weren’t enough obstacles to keep me from doing that.

Do you have any new projects, or developments in the pipeline?

No. I mostly don’t plan ahead. It’s hard for me to focus on my work if I’m thinking “after I’m done with this, I’ll be working on _____.” There are exceptions, like if I have a commission that I need to work on in the future, or if two projects occur to me at about the same time, but mostly, my YouTube viewers learn about what I’m working on just a few days after I do.

And finally, what does Beethoven’s music mean to you?

Some of the most thrilling, moving, fascinating, magical, intense moments of my life have happened while listening to (or playing) his music.

A.K.