‘The young Englishman, who knew all of Beethoven’s works by heart’

I believe we can all appreciate the Englishman’s justified admiration and enthusiasm for Beethoven’s musical talent and be somewhat bemused by the comment made to Potter, by pianist J.B Cramer:

‘If Beethoven emptied his inkstand upon a piece of music paper you would admire it!

Though, wouldn’t we all, Friends? Cramer, whom Beethoven respected greatly, was responsible for planting the wish in Potter’s mind to meet Beethoven and possibly become his student.

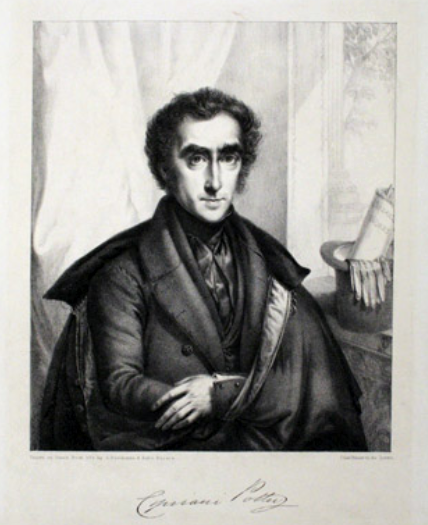

Cipriani Potter: Pianist, educator and composer in his own right

Cipriani Potter (1792-1871) was an English pianist, composer, conductor and teacher, born into a musical and flute-maker family. Potter began studying music at seven years of age, initially learning from his father, who played the violin and flute. Thomas Attwood and William Crotch gave Potter further musical instruction.

Later, he spent five years under the tutelage of Joseph Woelfl, the talented Austrian pianist and composer, who rivalled Beethoven in his extraordinary skills as a pianist. A teenager during this time, Potter studied and played a diverse range of pieces, including the entire Well-Tempered Clavier by J.S Bach. However, already at this tender age, Potter could be found practising Beethoven’s compositions, as we can see in an article published in 1871 by Henry C. Lunn in The Musical Times:

‘Woelfl… often reproved him [Potter] when he discovered that, instead of devoting himself to the pieces he had chosen for him, he was constantly practising Beethoven’s then little-known Sonatas, and revelling in the new world of thought which they conjured up…’

Indeed, Potter was a great admirer of Beethoven, however, he also respected Woelfl, to whom he attributed his fortepiano skills as player and composer, and who inspired him in subsequent years as an educator.

During his highly successful career, Cipriani Potter both composed and performed as a member of the Philharmonic Society, and taught from 1822 at the Royal Academy of Music, where he was later principal for almost three decades. Potter is in a significant way responsible for Beethoven’s influence in England. For example, he brought the joy of Beethoven’s third and fourth piano concertos to the English for the first time. An 1884 article in The Musical World tells us of Potter’s enthusiasm for Beethoven’s works even though

‘it was the custom of the time to cry out against these [works] in London…that the author [Beethoven] was a madman, and that the music had no interest in it.’

He appreciated and taught his students Beethoven’s late works which were so dismissively regarded in those times. Due to his significant educational efforts, his commitment to composing declined in his 30s. Nevertheless, we can find nine symphonies, four piano concertos and several pieces written for solo piano amongst his great musical legacy.

His travels to Germany, Austria and Italy were to have a significant influence on his musical endeavors. One of which we will discuss in this article, that of his great fortune in crossing paths with Beethoven himself at the age of 26.

Potter meets Beethoven

In search of fresh musical inspiration and opportunities, Potter travelled to Vienna in 1817, hoping to become a student of Beethoven. Thriving in the rich musical environment of the city at this time, Potter wrote three complete piano sonatas during these busy months.

In a letter to his secretary Ferdinand Ries, Beethoven wrote:

“Potter called on me several times; he seems to be a worthy man, and to have a talent for composition.”

Alas, Potter did not become Beethoven’s student. Beethoven instead recommended he study under his friend Aloys Forster. However, they often walked in the Viennese countryside together, speaking in Italian to each other. Their conversations were not only of a musical nature. Potter pointed out that Beethoven was an anglophile, and that he was very keen to visit England, and in particular, the Houses of Parliament. In terms of musical guidance, however, Beethoven offered to look over Potter’s compositions and did give his advice on these.

Recollections of Beethoven: The Musical World, 1836, (reprinted in The Musical Times in 1861)

Potter gives a spectacular, glowing description of Beethoven’s originality in his article in 1836, detailing his unique musical talent, whilst painting a picture of his character in a manner that attempts to correct public opinion, showing a great degree of understanding and empathy towards the composer.

Potter succinctly describes this originality, and freedom to compose outside of the distinctive style of the time, writing that:

“No author is so free of the charge of mannerism as Beethoven.”

Potter again demonstrates his sensitive approach to Beethoven both as human being and musical genius in the following insightful paragraph:

“If we may be allowed to imagine a man’s native character to be exhibited in his productions; in the compositions of Beethoven we shall frequently perceive it to be perfectly delineated. For instance; his Ops. 90 and 101, two sonatas abounding in his singularity of style; – containing the most amiable thoughts, intense feeling, and passion, with a decided melancholy pervading the whole. Persons not endued with a portion of these feelings, (particularly the last-named) or not possessing a very strong passion for music in the abstracts, cannot sympathize with the author, or appreciate his digressions in these instances from the conventional form of sonata-writing.”

Potter describes Beethoven as having a kind heart and a great depth of emotional experience. He acknowledges his, at times, irritable and passionate disposition, but attributes these entirely to his loss of hearing and the painful experience of losing the ability to delicately express sounds as a pianist. He writes about how misunderstood Beethoven was, due to erroneous descriptions of him by dissatisfied visitors, who in fact interrupted him at crucial moments of flow, coming to the capital out of misplaced curiosity, as opposed to genuine musical interest. He writes about Beethoven’s prowess at producing convincing orchestral effects throughout the entirety of his career, with the example of the 9th Symphony strongly demonstrating this.

Learning happens both ways

As a neat little example of the way learning often happens in both directions, in a detailed comparison of two pieces of music by Potter and Beethoven, it has even been suggested that Beethoven was in fact influenced by his English contemporary, and not just the other way round! Perhaps you can spot it too, in the final trills of Beethoven’s Sonata Op. 109 and Potter’s Op.3!

A.K.