Every July (14th July) France celebrates its Fête nationale française, the French National Holiday. In English-speaking countries the Bastille Day (since 1789). It is the day of the storming of the Bastille, a major event during the French Revolution. Like so many social changes in history this one also was rooted in economic crisis, or hunger being the name on the streets. After a stormy period covered with blood, on 4th August 1789 feudalism was abolished and on the 26th the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (Déclaration des Droits de l’Homme et du Citoyen) was proclaimed.

How the Revolution influenced culture and arts?

The French Revolution had significant impact on culture, both in France and beyond. Nationalism was a strong driving force behind the changes. A new, unified French nation, and this idea of national identity was reflected in art, literature, and music. Painter-propagandist Jacques-Louis David, also member of the National Convention, coordinated the utilization of these ancient or new symbols.

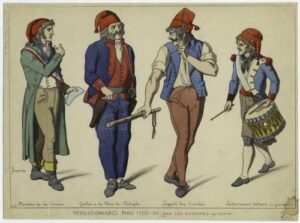

The red-white-blue tricolor appeared not only as cockades or flag, but also in the radically changing fashion, too. Ornate costumes of the aristocracy had largely disappeared by 1791. Women stopped wearing hooped skirts and large headdresses, while men abandoned the use of powdered wigs. Simple and restrained dress, previously worn by the working class, became the fashion.

Language of everyday life also underwent significant changes. Instead of Monsieur and Madame the term citizen was the way to address each other. Bows, curtseys and the doffing of hats were all abandoned.

Subject matter in art shifted towards practical, social or political subjects, common in all to manifest the spirit of the Revolution. Artists embraced the neoclassical style, which put emphasis on noble themes, virtue and personal sacrifice, mostly inspired by ancient Greece and Rome.

The Revolution found its way also into literature, poetry and music. The tone of these works started out as moderate and optimistic, but following the Revolution itself, later became violent and radical. The most famous of all revolutionary songs, was the La Marseillaise, written in 1792 by army engineer Rouget de Lisle. It was so popular that in 1795 was adopted as the French national anthem.

How the French Revolution influenced Beethoven and his music?

Although Beethoven as adult lived in Vienna, his home town for his first twenty years used to be Bonn. This city, despite speaking German and being part of the Holy Roman Empire, was closer in spirit to Paris than to Vienna (capital of the Empire). Young Beethoven, as a consequence, was heavily exposed to the Enlightenment and the ideas leading up to the French Revolution. This spark was brought inside him to the heart of the Empire and he let it manifest in his music. Igor Stravinsky wrote about him,

“Beethoven is the friend and contemporary of the French Revolution, and he remained faithful to it even when, during the Jacobin dictatorship, humanitarians with weak nerves of the Schiller type turned from it, preferring to destroy tyrants on the theatrical stage with the help of cardboard swords. Beethoven, that plebeian genius, who proudly turned his back on emperors, princes and magnates – that is the Beethoven we love for his unassailable optimism, his virile sadness, for the inspired pathos of his struggle, and for his iron will which enabled him to seize destiny by the throat.”

Covering this subject in completeness is beyond the frames of this article, but we can narrow it down to a few interesting points.

We know that the ideas of the Revolution resonated with Beethoven, especially freedom and equality, the belief in the power of the individual to shape history. His music similarly breaks from the constrains of the classical music forms, expanding the possibilities of expression through his use of innovative techniques and emotional depth.

Flow of information in those times was slow and often difficult, nevertheless Beethoven followed the developments in France. We know he was in contact with diplomats, musicians and other intellectuals traveling to or via Vienna. We also know that he was in possession of musical scores of the Revolution.

Paramount proof of his feelings towards the developments in France was his Third Symphony, the so called Eroica (Hero). Based on incomplete and often confusing news, like many others, he had the impression that Napoleon was the defender of the Revolution and human rights. With this in mind he created a truly revolutionary music that he dedicated to Napoleon.

The Eroica was a groundbreaking work that opened the doorway to Beethoven’s new path in his composing. Only the first movement is longer in time than the usual four-movement symphonies of the era. The score is so complex and difficult to play that the musicians who had to play it were shocked at first. Another novelty was the introduction of a theme, a message that the music was supposed to say. In this case a hero, who struggles for a revolution. The music is full with clashes, victories and defeats, heroism and death. It is the Revolution itself.

When in 1804 the news broke in Vienna about Napoleon becoming Emperor, Beethoven was devastated. In his anger he crossed out his dedication and changed the name to Eroica – in the memory of a great man.

Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony is another piece of music about struggle and triumph. The well known first four notes and some of the popular musical themes, many believe, may have roots in French revolutionary songs.

His only opera Fidelio, beside the romantic line in the story, also has revolutionary overtones. Look no further than the singing chorus of the political prisoners approaching daylight from their dungeons:

“Oh what joy, in the open air

Freely to breathe again!

Up here alone is life!

The dungeon is a grave.”

His final and his biggest statement is in his last, the Ninth Symphony. This is based on Schiller’s famous Ode to Joy, a hymn to the humanist utopia of the equality of all humankind. In the famous choral part says, Alle Menschen werden Brüder (All people become brothers), which can be understood as Beethoven’s final message to humanity. The Ninth is often called the The Marseillaise of Humanity.