With enough certainty we know that on his deathbed Beethoven had with him some books from Plutarch, Homer, Ovid and Epictetus. In this article we will discover who was Epictetus and how he – and stoic philosophy in general – influenced his approach to emotions.

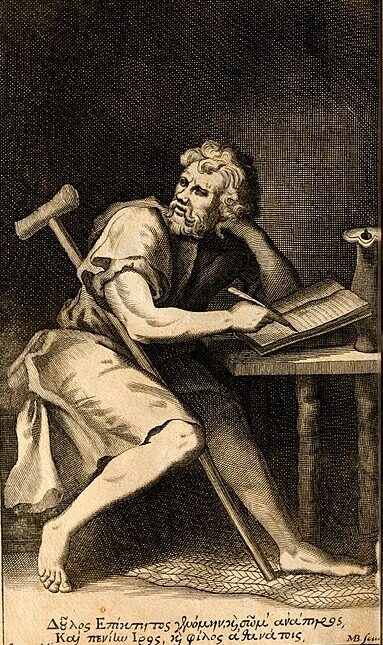

Who was Epictetus?

Epictetus was a Greek philosopher born around 50 AD in Phrygia (today in Turkey). His name given by his parents is unknown, the Greek word epictetus simply means acquired. The name fits, as he spent his youth as a slave in Rome, at the house of Epaphroditus, who was the secretary of the emperor Nero.

Epictetus loved philosophy and learned from Musonius Rufus. After he was freed, sometime AD 68, he began teaching philosophy in Rome. When the ruthless, but efficient autocrat emperor Domitian banished all philosophers from Rome, Epictetus went to Nicopolis (Greece) and started his own school. His most famous pupil was Arrian, who described his master as a powerful speaker, whose company even emperor Hadrian sought.

Epictetus was disabled, often portrayed with crutch. According to some sources his master broke his leg, others state that he was like this from childhood. He lived in great simplicity and died around AD 135.

Epictetus was a practical philosopher. For him philosophy was not theory, but a way of life. He emphasized that one should focus on things he owns and controls, the rest should be accepted dispassionately, which can be achieved by self-discipline.

What could Beethoven learn from Epictetus?

Around 1816 Beethoven wrote in his Tagebuch (diary),

“Blessed is the man who has suppressed all his passions, and who subsequently carries out all affairs of daily life with decisiveness, unconcerned about the outcome!”

In Beethoven’s time Vienna, in fact the whole German-speaking part of Europe, was in ‘Graecomanie’, as Schiller put it. It was the great Greek revival of thought. Beethoven was acquainted with Greek literature and philosophy from his childhood, a connection he cultivated all his life. Schindler testifies to that, when wrote to Moscheles that “when alone, he entertains himself with reading the ancient Greeks”. He knew ancient stoic philosophy and in many ways he was challenged by them.

Epictetus had three main pillars, or training, for his students to practice. First, the management of desires and aversions. Second, the management of impulses and choices. Third, the control over one’s own assent. Beethoven, the passionate, often moody, sometimes rude man had something to learn here!

As for the first pillar, Epictetus says we should not desire things that are unattainable to us and we should never run away from unavoidable. Today, most people would say they desire first and foremost health, happiness and probably wealth. For a Stoic philosopher these are mostly irrelevant and they seek wisdom as the only true good. For example money can be used for good and evil purposes, too. Not good or evil in itself.

Epictetus says, we should focus on what we can influence in life:

“Of these [three areas of study], the principle, and most urgent, is that which has to do with the passions; for these are produced in no other way than by the disappointment of our desires, and the incurring of our aversions. It is this that introduces disturbances, tumults, misfortunes, and calamities; and causes sorrow, lamentation and envy; and renders us envious and jealous, and thus incapable of listening to reason.”

This is all about priorities and focus. Setting our value system right and follow them, as for the rest we have little or no influence.

The second pillar is about acting and relations with others. Epictetus says,

“The [second area of study] has to do with appropriate action. For I should not be unfeeling like a statue, but should preserve my natural and acquired relations as a man who honours the gods, as a son, as a brother, as a father, as a citizen.”

and

“Appropriate acts are in general measured by the relations they are concerned with. ‘He is your father.’ This means that you are called upon to take care of him, give way to him in all things, bear with him if he reviles or strikes you.

‘But he is a bad father.’

Well, have you any natural claim to a good father? No, only to a father.

‘My brother wrongs me.’

Be careful then to maintain the relation you hold to him, and do not consider what he does, but what you must do if your purpose is to keep in accord with nature.”

In other words, our actions must be motivated not only by our desire to be rational and excellent, but also by our obligations we have in our relationships. He says, “Further, we must remember who we are, and by what name we are called, and must try to direct our acts to fit each situation and its possibilities.” In other words, the name citizen, or son, or brother are names that if considered rightly, will point us in the good direction in our actions.

The third pillar of Epictetus is the discipline of assent. Assent comes from the Greek word sunkatathesis, meaning approve or agree. In this discipline, we first ought to interpret and judge our impressions, only after that accept them as reality.

“Make it your study then to confront every harsh impression with the words, ‘You are but an impression, and not at all what you seem to be’. Then test it by those rules that you possess; and first by this–the chief test of all–’Is it concerned with what is in our power or with what is not in our power?’ And if it is concerned with what is not in our power, be ready with the answer that it is nothing to you.”

Epictetus considers this third area the utterly important, as this secures the first two. If we fail to evaluate our impression correctly, we may end up desiring the wrong things and acting inappropriately.

For Beethoven to navigate the problem of passions had to be a challenge. He must have realized that self-control is one area where he must improve. In a letter in 1804 he wrote, “Plutarch helps me with restraining my passions.” He also rejected the obsession of material desires, he distanced himself from luxury and extravaganza. Once he was reported saying in a restaurant, “Why so many dishes? Man is certainly very little higher than the other animals if his chief delights are those of the table.”