Take a showman and inventor, add a grumpy genius composer, shake it well and see what happens! Read on to discover this friendship and the achievements they realized together!

Who was Johann Maelzel?

Maelzel (sometimes Mälzel, August 15, 1772 – July 21, 1838) was a German inventor, born in Regensburg. His father was an organ builder who made sure the son receives proper education in music. It was not only music he soaked up in childhood, but the passion (and ability) to build complex machines. In 1792 he moved to Vienna, the first destination of many voyages to come. Here, after considerable amount of experimenting, he had created more mechanical musical inventions that made him a celebrity across Europe. As a result, he was appointed as imperial court-mechanician for the Emperor in Vienna.

Later in his life he moved to Paris (1816), where he became the producer of the Maelzel Metronomes, then he was on the move again, first to Munich and later to Vienna, again. As his last act, he established an enterprise and set to America exhibiting and promoting his inventions. He toured there for more than a decade with respectable success. In 1838 he died on a ship harbouring in Venezuela. The probable cause of death was alcohol poisoning.

The inventions of Johann Maelzel

Maelzel was a complex character. Not only was he a brilliant creator of mechanisms, conversant with music, but a showman, too! He knew how publicity works and was very skilful in presenting his machines.

Panharmonicon

Maelzel, in 1805, invented the Panharmonicon, which is a musical machine that can imitate orchestral instruments. This specific Panharmonicon was able to make sounds like gunfire or cannon shots. This came handy when Beethoven composed his Wellington’s Victory (Op. 91) during which shots are to be made. One of Maelzel’s Panharmonicon was sent to Boston (USA) in 1811 with which he toured the country till his death.

The Maelzel Orchestrion

Orchestrion is a machine that plays music. It is supposed to sound like a band or orchestra. The operation is synchronized by a pinned cylinder, sometimes by music roll or book. The sound in such machines are usually produced by pipes, but often accompanied by a piano, drum, cymbal, triangle and tambourine.

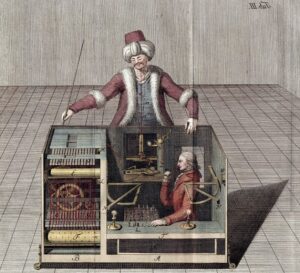

The Turk – the Automaton Chess-player

The Turk was a – fraudulent – machine that played chess. Originally it was not the invention of Maelzel, but of a Hungarian inventor Wolfgang von Kempelen. The machine consisted of a life-sized Turk model, dressed in Ottoman robes and turban. The machine was the perfect illusion. Opening the doors on the base of the machine one could observe gears and cogs, but in reality a human chess master was hiding inside, operating the Turk.

Maelzel purchased the machine in 1804 from the son of Kempelen on half the price on which his father was willing to sell. Maelzel made repairs and improvements on the Turk and toured with it for the rest of his life. The Turk had difficult and sometimes famous opponents during his career, most notably Napoleon and Benjamin Franklin.

Ear trumpets for Beethoven

After reaching a certain level of deafness Beethoven welcomed every opportunity, medical or else, that promised a way out or at least improvement of his condition. One aid that for a time really helped him was the ear trumpet. Beethoven used more kinds, but he preferred the ones Maelzel prepared for him.

|Related: The ear trumpets of Beethoven

The metronome

Maelzel was not the first to invent a metronome like machine, but he was the one who made it perfect. He made a copy of Nikolaus Winkel’s innovation and perfected it into the Maelzel Metronome, something that he later protected by copyrights.

|Related: The metronome

Automaton Trumpeter

Yet another musical machine by Maelzel. This was able to use a trumpet, with lifelike movements, and mostly played military field signals.

Beethoven and Maelzel

When Maelzel (sometimes Mälzel) first approached Beethoven, the composer was in the abyss of depression. His offer was a cooperation: Beethoven would compose a piece for Maelzel’s mechanical instrument, his Panharmonicon. This commemorative musical composition is the Wellington’s Victory or The Battle of Vitoria, celebrating the duke of Wellington’s victory over the French and Napoleon in Spain at the Battle of Vitoria. Maybe because of his bad mood, maybe the novelty and interesting nature of these machines, Beethoven accepted the offer.

The result was success, so much so, that the two decided to extend this music into a complete orchestral version that would include arms and artillery along the musical instruments. Being a real showman, Maelzel made suggestions for the composition. How much was the final product influenced by him and how original Beethoven it remained, is unknown. This question soon turned into an ugly dispute between them…

The premier of Wellington’s Victory was in December 1813, during the Congress of Vienna, the largest diplomatic get together in history (victors of the Napoleonic wars gathered to decide about the future of Europe). The concert was a benefit event to help the war wounded.

The audience, and in fact whole Vienna, went crazy about this performance! Despite the success of this mainstream piece, its value and quality is questionable. The notes are by a master composer, but the inspiration is from a showman. Even Beethoven himself called it years later nothing, but an occasional work.

As so often happens, the friendship (temporarily) ended because of money. Maelzel believed he had a share in all income the Wellington’s Victory makes, since he was the originator of the idea and had a fair share in the creative process. Beethoven believed otherwise and refused to give Maelzel any copy of the piece. The inventor, in response, took some parts of the score in his possession, somehow completed them and went on to Munich to promote and put on the show.

Beethoven was furious! He went to a lawyer, to the court, put out an official statement* and did his best to discredit Maelzel, about whom he said, “rude fellow, wholly without education or breeding”. He even claimed that the Maelzel ear trumpets were useless (something in fact was not true as he at the time used them regularly).

Without considering all written evidence at hand about the origins of this musical piece or the fair share of copyrights, it is worth citing one witness who can shed light on this matter. It is Ignaz (Isaac) Moscheles who has this to say,

“I witnessed the origin and progress of this work, and remember that not only did Mälzel decidedly induce Beethoven to write it, but even laid before him the whole design of it; himself wrote all the drum-marches and the trumpet-flourishes of the French and English armies; gave the composer some hints, how he should herald the English army by the tune of “Rule Britannia”;…”

Unfortunately, we have no testimony of the case from Maelzel, but we do know that some time later the two men reconciled and all the legal expenses were settled equally by the two parties.

The next chapter in their renewed cooperation was the metronome. Although the invention was not of Maelzel, he perfected it and protected his version with patent. The inventor was keen to have the professional backing of prominent figures of music, especially Beethoven’s. At first, Beethoven was no enthusiastic about the device, saying “it is silly stuff; one must feel the tempos”, nevertheless he stood with Salieri recommending the metronome.

If the realization of its usefulness or the willingness to support an old friend, it is unknown, but Beethoven finally stood behind this novelty and published the tempo markings for all his symphonies (eight at that time) in the Leipsic “Allgemeine Musik-Zeitung” on December 17, 1813. Even years later, in 1818 he joined Salieri – again – in a public announcement in the Wiener Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung, promoting the metronome and stating that it is indispensable for students of all musical instruments and even for singers.

After 1818 Maelzel had left Vienna for his exhibition tour and thus left behind the European continent all together. In North-America he enjoyed great success with his inventions and shows until his death in 1838.

* This is a longer account from Beethoven about the dispute on the copyrights

Deposition

Of my own volition I had composed a Battle Symphony for Mälzel for his Panharmonica without pay. After he had had it for a while he brought me the score, the engraving of which he had already begun [Beethoven probably meant the preparation of the cylinder] and wanted it arranged for full orchestra. I had previously formed the idea of a Battle (Music) which, however, was not applicable to his Panharmonica. We agreed to perform this work and others of mine in a concert for the benefit of the soldiers. Meanwhile I got into the most terrible financial embarrassment. Deserted by the whole world here in Vienna, in expectation of a bill of exchange, etc., Mälzel offered me 50 ducats in gold. I took them and told him that I would give them back to him here, or would let him take the work with him to London in case I did not go with him—in which latter case I would refer him to an English publisher who would pay him these 50 ducats. The Academies were now given. In the meantime Mälzel’s plan and character were developed. Without my consent he printed on the placards that it was his property. Incensed at this he had to have these torn down. Now he printed: “Out of friendship for his journey to London”; to this I consented, because I thought that I was still at liberty to fix the conditions on which I would let him have the work. I remember that I quarrelled violently with him while the notices were printing, but the too short time—I was still writing on the work. In the heat of my inspiration, immersed in my work, I scarcely thought of Mälzel. Immediately after the first Academy in the University Hall [the premier], I was told on all hands by trustworthy persons that Mälzel was spreading it broadcast that he had loaned me 400 ducats in gold. I thereupon had the following printed in the newspaper, but the newspaper writers did not print it as Mälzel is befriended with all of them. Immediately after the first Academy I gave back to Mälzel his 50 ducats, telling him that having learned his character here, I would never travel with him, righteously enraged because he had printed on the placards, without my consent, that all the arrangements for the Academy were badly made and his bad patriotic character showed itself in the following expressions—I [unreadable]—if only they will say in London that the public here paid 10 florins; not for the wounded but for this did I do this—and also that I would not let him have the work for London except on conditions concerning which I would let him know. He now asserted that it was a gift of friendship and had this expression printed in the newspaper without asking me about it in the least. Inasmuch as Mälzel is a coarse fellow, entirely without education, or culture, it may easily be imagined how he conducted himself toward me during this period and increased my anger more and more. And who would force a gift of friendship upon such a fellow? I was now offered an opportunity to send the work to the Prince Regent. It was now impossible to give him the work unconditionally. He then came to you and made proposals. He was told on what day to come for his answer; but he did not come, went away and performed the work in Munich. How did he get it? Theft was impossible—Herr Mälzel had a few of the parts at home for a few days and from these he had the whole put together by some musical handicraftsman, and with this he is now trading around in the world. Herr Mälzel promised me hearing machines. To encourage him I composed the Victory Symphony for his Panharmonica. His machines were finally finished, but were useless for me. For this small trouble Herr Mälzel thinks that after I had set the Victory Symphony for grand orchestra and composed the Battle for it, I ought to have him the sole owner of this work. Now, assuming that I really felt under some obligation for the hearing machines, it is cancelled by the fact that he made at least 500 florins convention coin, out of the Battle stolen from me or compiled in a mutilated manner. He has therefore paid himself. He had the audacity to say here that he had the Battle; indeed he showed it in writing to several persons—but I did not believe it, and I was right, inasmuch as the whole was not compiled by me but by another. Moreover, the honor which he credits to himself alone might be a reward. I was not mentioned at all by the Court War Council, and yet everything in the two academies was of my composition. If, as he said, Herr Mälzel delayed his journey to London because of the Battle, it was merely a hoax. Herr Mälzel remained until he had finished his patchwork (?), the first attempts not being successful.

Beethoven,